- The dimensions of Hindu nationalism in India

- India’s Muslims express pride in being Indian while identifying communal tensions, desiring segregation

- Muslims, Hindus diverge over legacy of Partition

- Religious conversion in India

- Religion very important across India’s religious groups

- Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived

- Across India’s religious groups, widespread sharing of beliefs, practices, values

- Religious identity in India: Hindus divided on whether belief in God is required to be a Hindu, but most say eating beef is disqualifying

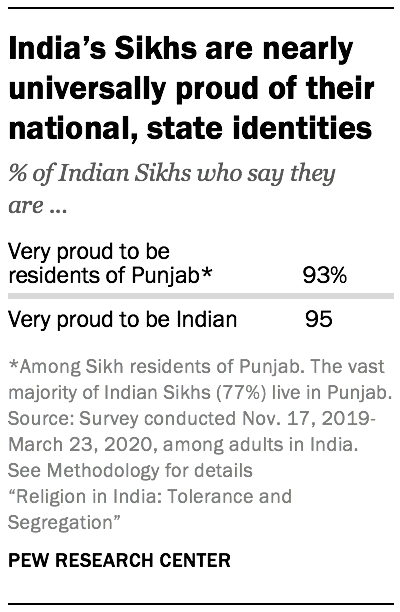

- Sikhs are proud to be Punjabi and Indian

- Most Indians say they and others are very free to practice their religion

- Most people do not see evidence of widespread religious discrimination in India

- Most Indians report no recent discrimination based on their religion

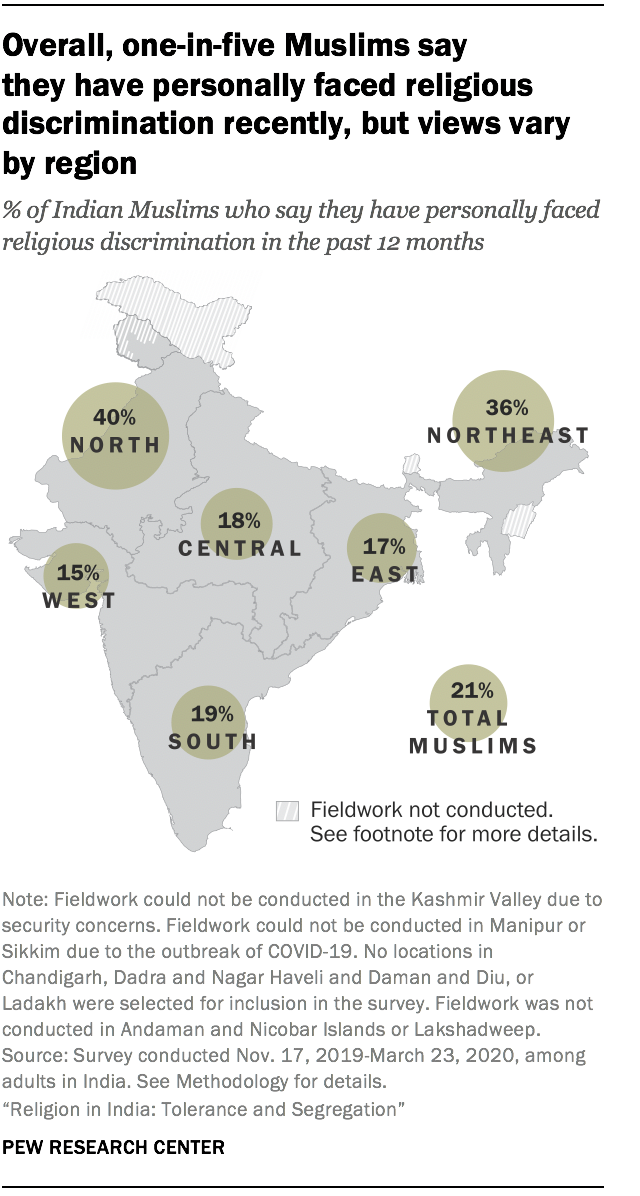

- In Northeast India, people perceive more religious discrimination

- Most Indians see communal violence as a very big problem in the country

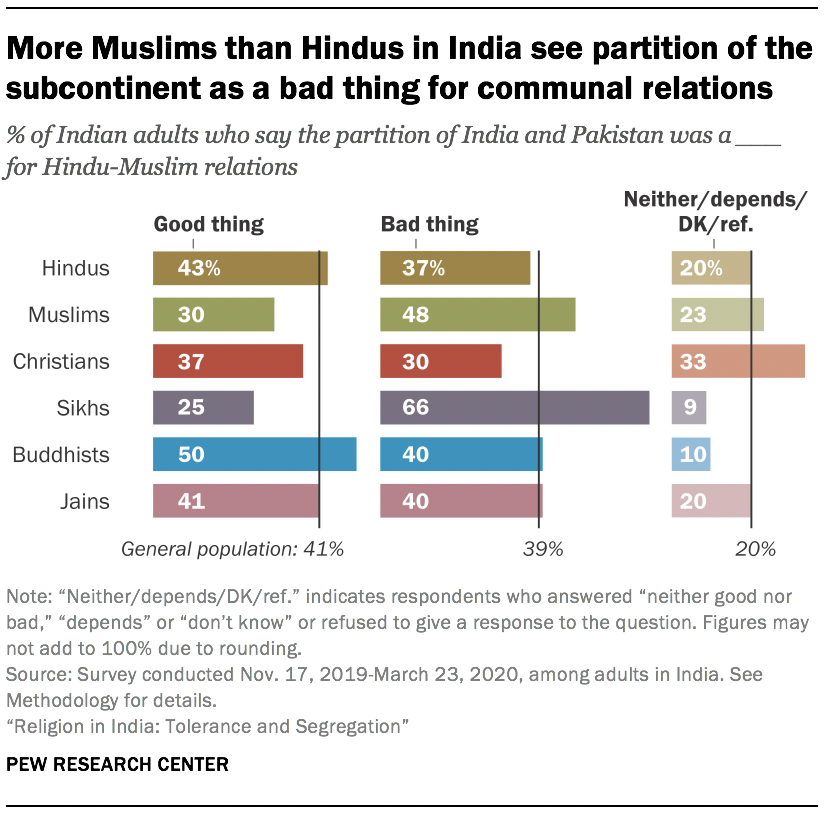

- Indians divided on the legacy of Partition for Hindu-Muslim relations

- More Indians say religious diversity benefits their country than say it is harmful

- Indians are highly knowledgeable about their own religion, less so about other religions

- Substantial shares of Buddhists, Sikhs say they have worshipped at religious venues other than their own

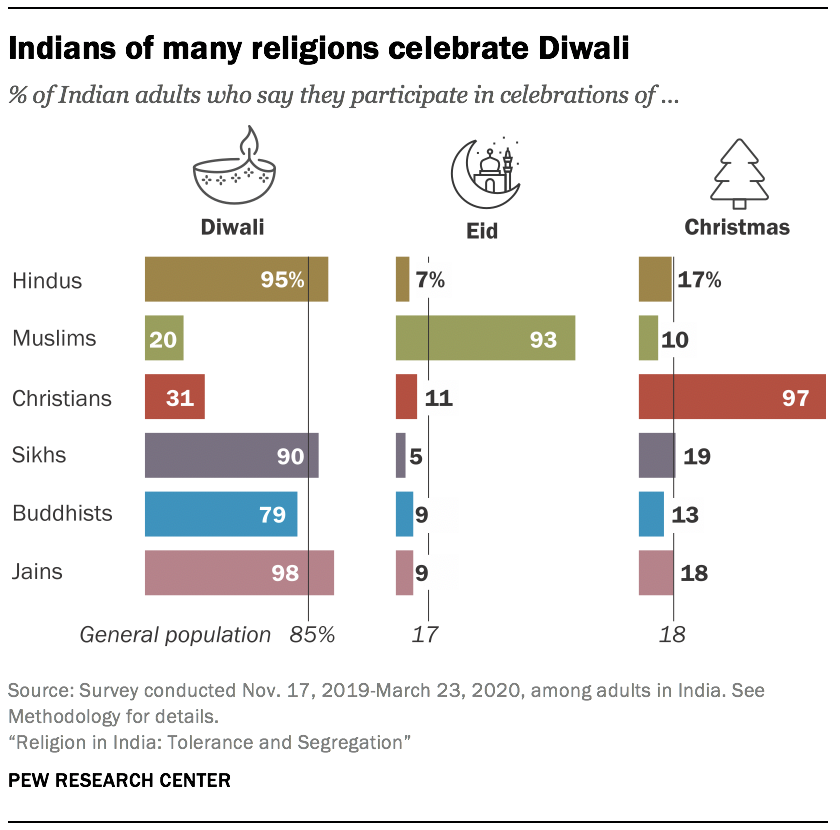

- One-in-five Muslims in India participate in celebrations of Diwali

- Members of both large and small religious groups mostly keep friendships within religious lines

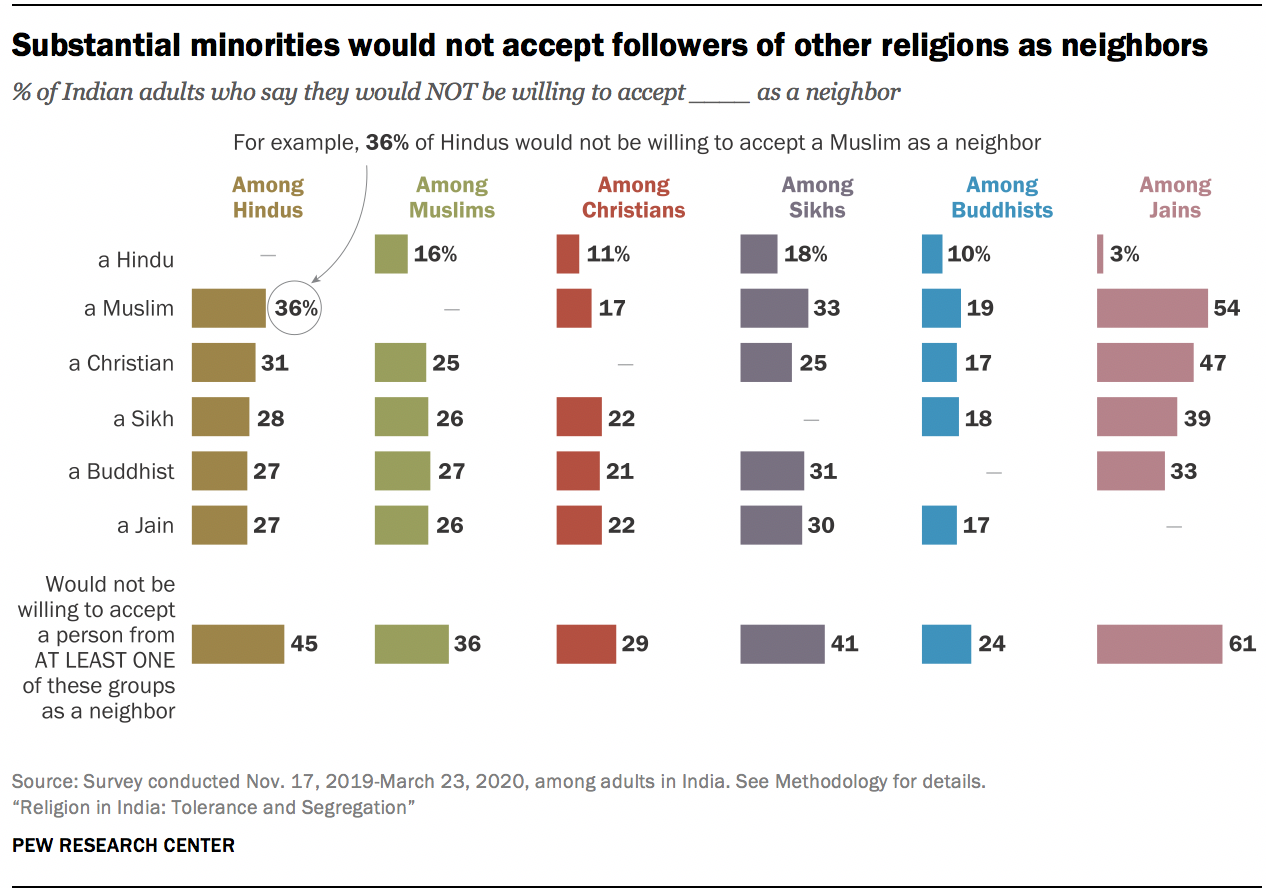

- Most Indians are willing to accept members of other religious communities as neighbors, but many express reservations

- Indians generally marry within same religion

- Most Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains strongly support stopping interreligious marriage

- India’s religious groups vary in their caste composition

- Indians in lower castes largely do not perceive widespread discrimination against their groups

- Most Indians do not have recent experience with caste discrimination

- Most Indians OK with Scheduled Caste neighbors

- Indians generally do not have many close friends in different castes

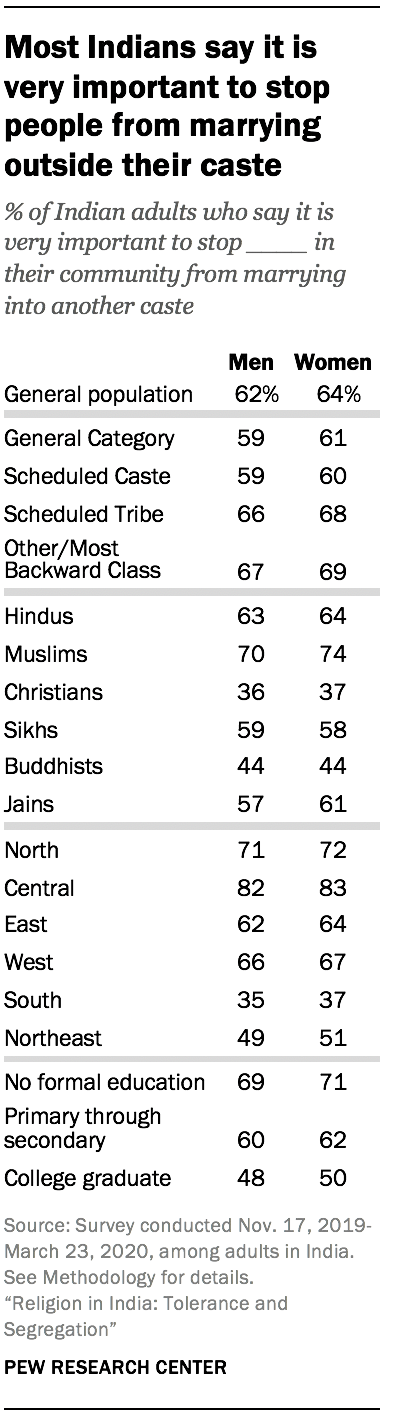

- Large shares of Indians say men, women should be stopped from marrying outside of their caste

- Most Indians say being a member of their religious group is not only about religion

- Common ground across major religious groups on what is essential to religious identity

- India’s religious groups vary on what disqualifies someone from their religion

- Hindus say eating beef, disrespecting India, celebrating Eid incompatible with being Hindu

- Muslims place stronger emphasis than Hindus on religious practices for identity

- Many Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists do not identify with a sect

- Sufism has at least some followers in every major Indian religious group

- Large majorities say Indian culture is superior to others

- What constitutes ‘true’ Indian identity?

- Large gaps between religious groups in 2019 election voting patterns

- No consensus on whether democracy or strong leader best suited to lead India

- Majorities support politicians being involved in religious matters

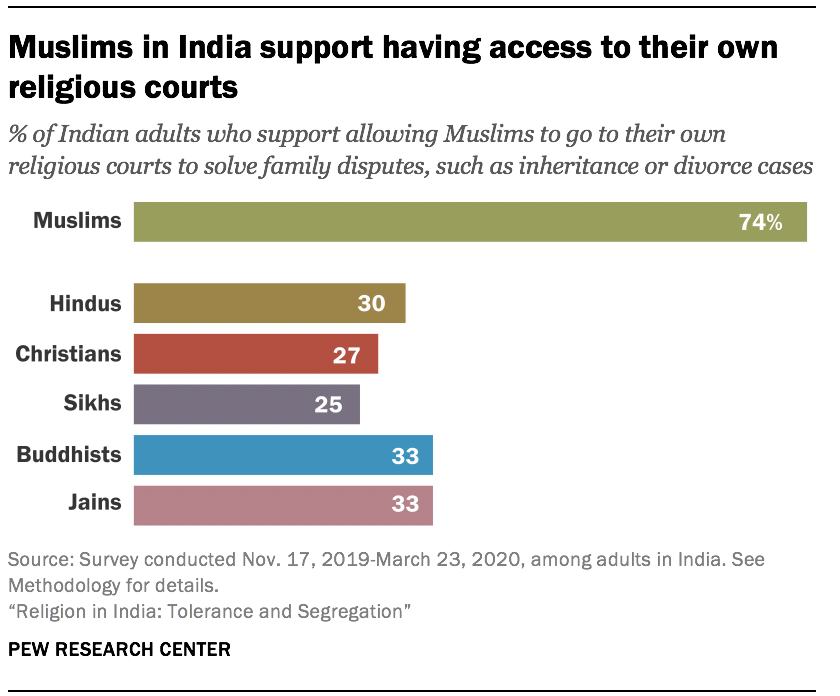

- Indian Muslims favor their own religious courts; other religious groups less supportive

- Most Indians do not support allowing triple talaq for Muslims

- Southern Indians least likely to say religion is very important in their life

- Most Indians give to charitable causes

- Majorities of Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Jains in India pray daily

- More Indians practice puja at home than at temple

- Most Hindus do not read or listen to religious books frequently

- Most Indians have an altar or shrine in their home for worship

- Religious pilgrimages common across most religious groups in India

- Most Hindus say they have received purification from a holy body of water

- Roughly half of Indian adults meditate at least weekly

- Only about a third of Indians ever practice yoga

- Nearly three-quarters of Christians sing devotionally

- Most Muslims and few Jains say they have participated in or witnessed animal sacrifice for religious purposes

- Most Indians schedule key life events based on auspicious dates

- About half of Indians watch religious programs weekly

- For Hindus, nationalism associated with greater religious observance

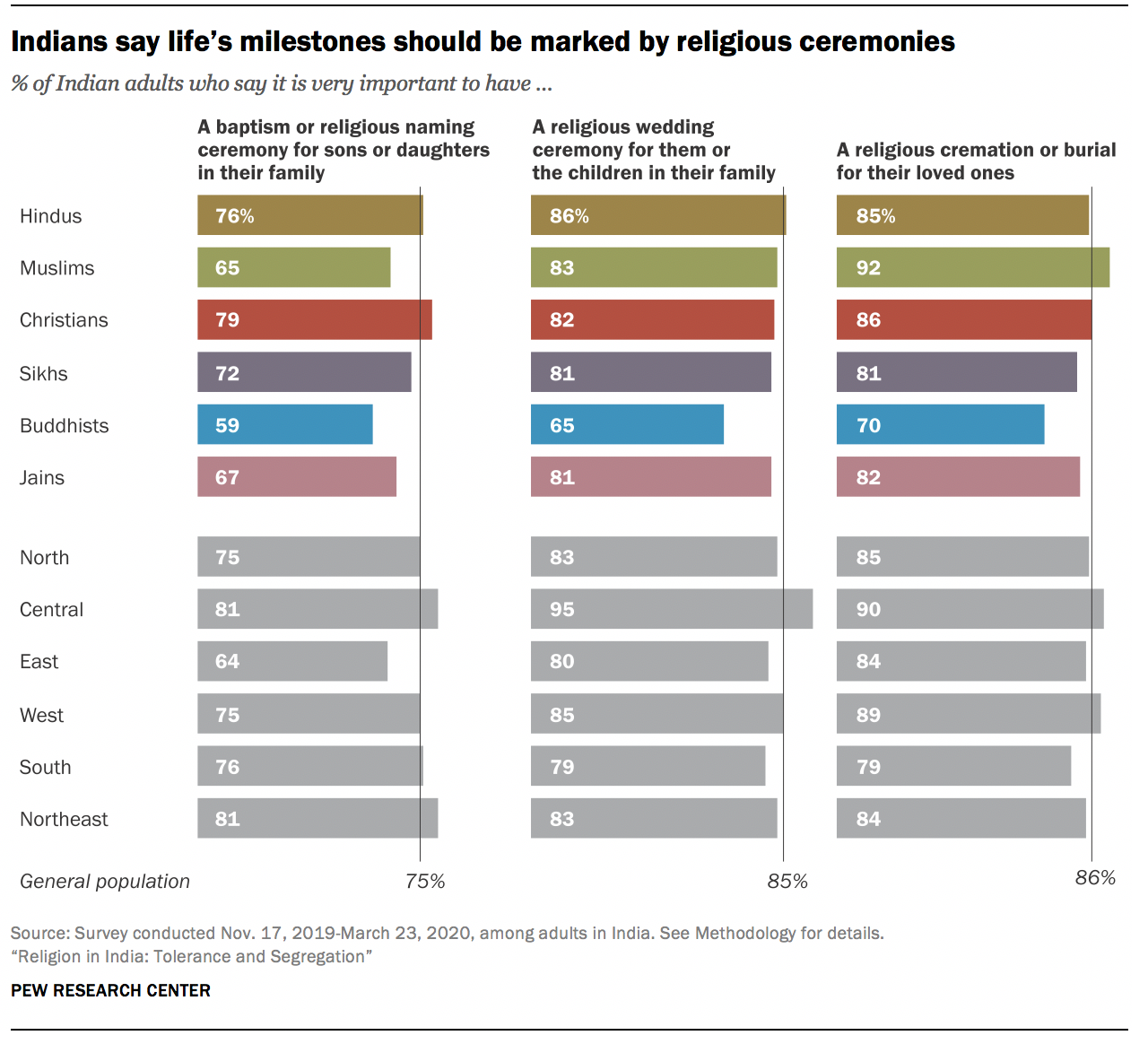

- Indians value marking lifecycle events with religious rituals

- Most Indian parents say they are raising their children in a religion

- Fewer than half of Indian parents say their children receive religious instruction outside the home

- Vast majority of Sikhs say it is very important that their children keep their hair long

- Half or more of Hindus, Muslims and Christians wear religious pendants

- Most Hindu, Muslim and Sikh women cover their heads outside the home

- Slim majority of Hindu men say they wear a tilak, fewer wear a janeu

- Eight-in-ten Muslim men in India wear a skullcap

- Majority of Sikh men wear a turban

- Muslim and Sikh men generally keep beards

- Most Indians are not vegetarians, but majorities do follow at least some restrictions on meat in their diet

- One-in-five Hindus abstain from eating root vegetables

- Fewer than half of vegetarian Hindus willing to eat in non-vegetarian settings

- Indians evenly split about willingness to eat meals with hosts who have different religious rules about food

- Majority of Indians say they fast

- More Hindus say there are multiple ways to interpret Hinduism than say there is only one true way

- Most Indians across different religious groups believe in karma

- Most Hindus, Jains believe in Ganges’ power to purify

- Belief in reincarnation is not widespread in India

- More Hindus and Jains than Sikhs believe in moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth)

- Most Hindus, Muslims, Christians believe in heaven

- Nearly half of Indian Christians believe in miracles

- Most Muslims in India believe in Judgment Day

- Most Indians believe in fate, fewer believe in astrology

- Many Hindus and Muslims say magic, witchcraft or sorcery can influence people’s lives

- Roughly half of Indians trust religious ritual to treat health problems

- Lower-caste Christians much more likely than General Category Christians to hold both Christian and non-Christian beliefs

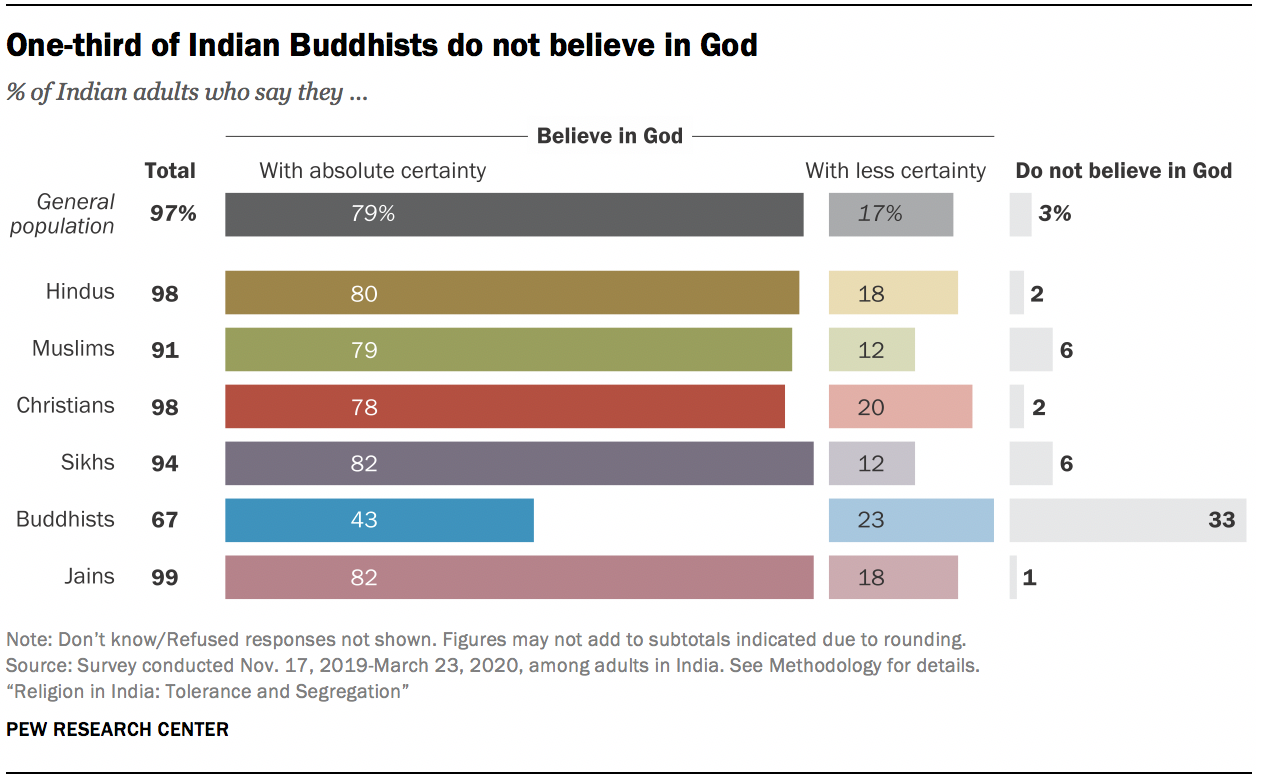

- Nearly all Indians believe in God

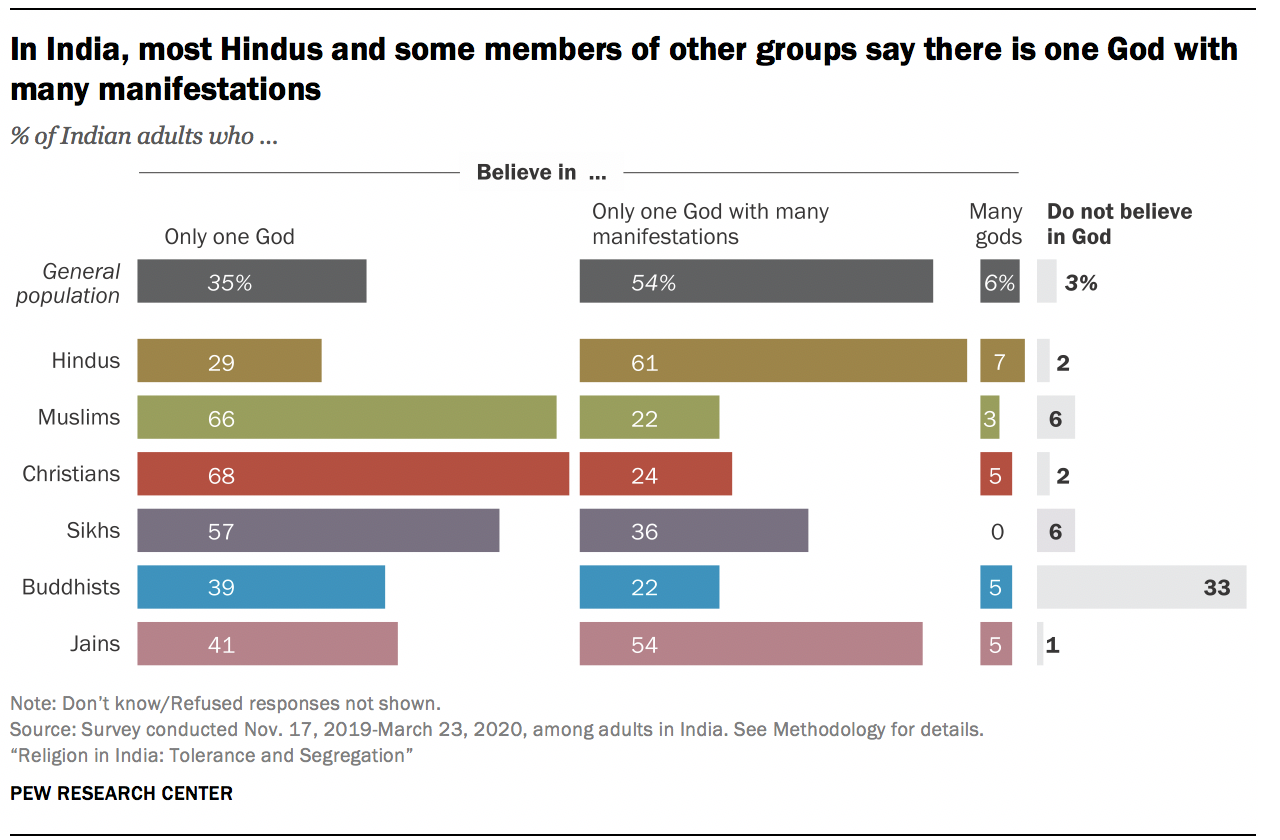

- Few Indians believe ‘there are many gods’

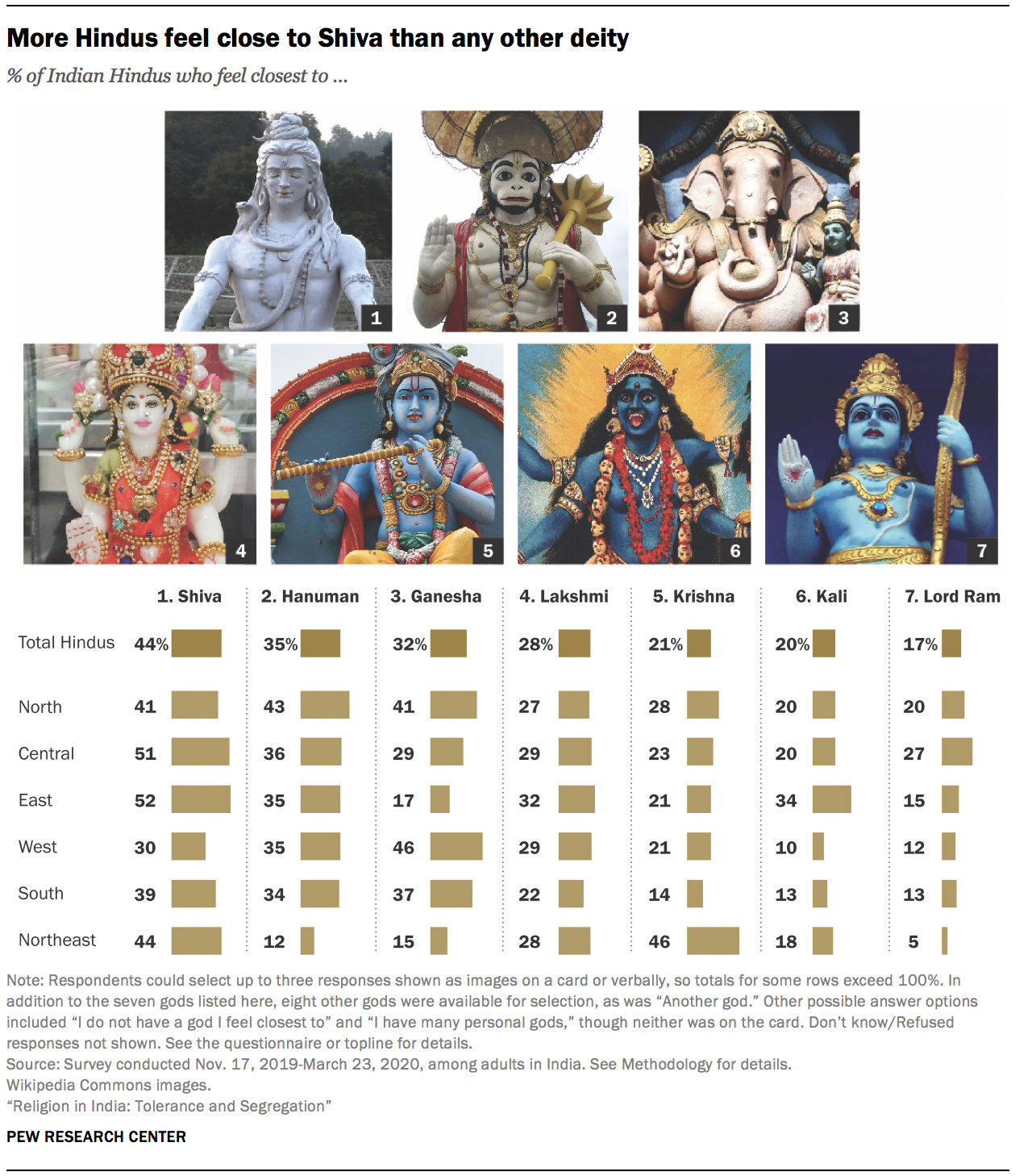

- Many Hindus feel close to Shiva

- Many Indians believe God can be manifested in other people

- Indians almost universally ask God for good health, prosperity, forgiveness

- Questionnaire design

- Sample design and weighting

- Precision of estimates

- Response rates

- Significant events during fieldwork

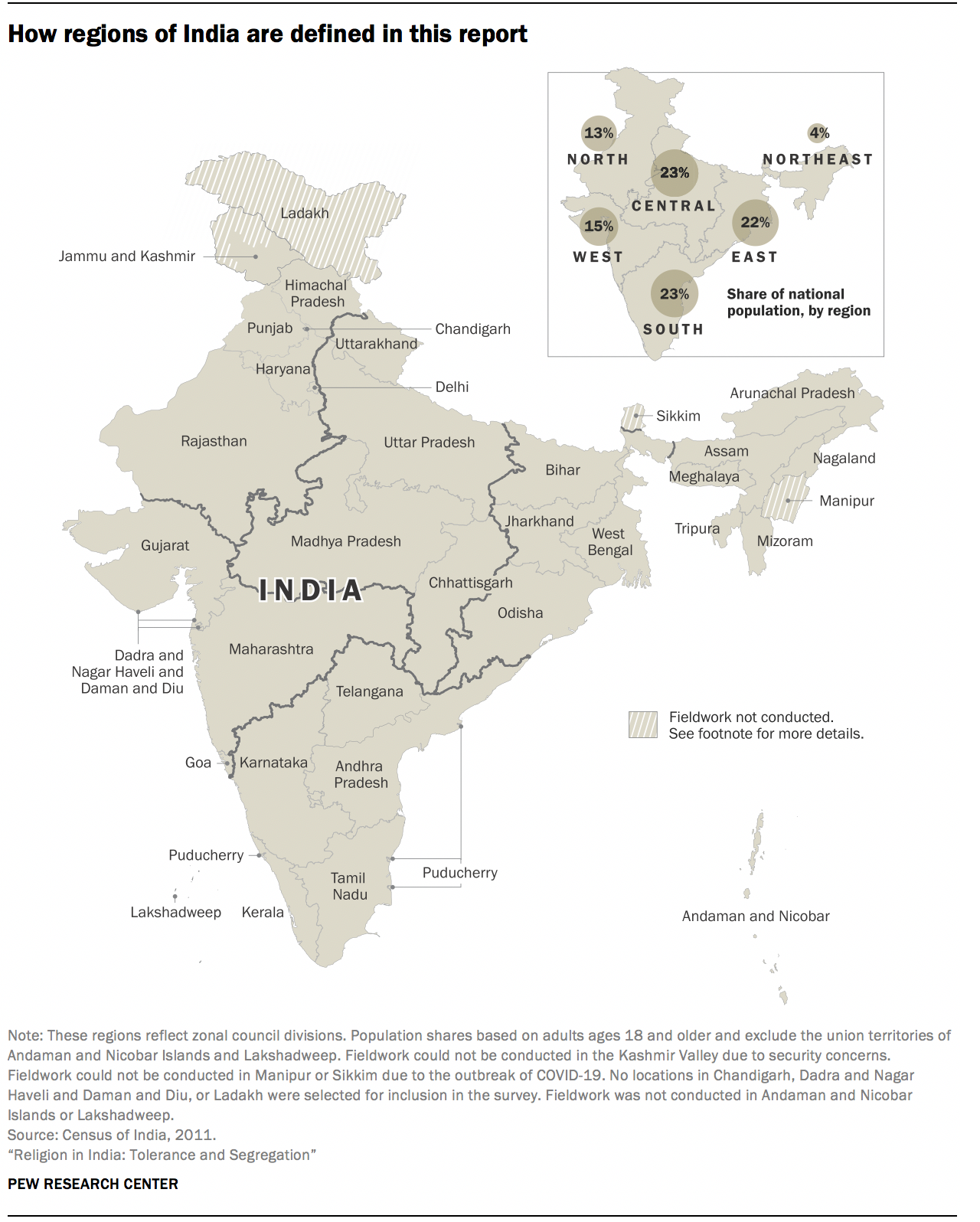

This study is Pew Research Center’s most comprehensive, in-depth exploration of India to date. For this report, we surveyed 29,999 Indian adults (including 22,975 who identify as Hindu, 3,336 who identify as Muslim, 1,782 who identify as Sikh, 1,011 who identify as Christian, 719 who identify as Buddhist, 109 who identify as Jain and 67 who identify as belonging to another religion or as religiously unaffiliated). Interviews for this nationally representative survey were conducted face-to-face under the direction of RTI International from Nov. 17, 2019, to March 23, 2020.

To improve respondent comprehension of survey questions and to ensure all questions were culturally appropriate, Pew Research Center followed a multi-phase questionnaire development process that included expert review, focus groups, cognitive interviews, a pretest and a regional pilot survey before the national survey. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into 16 languages, independently verified by professional linguists with native proficiency in regional dialects.

Respondents were selected using a probability-based sample design that would allow for robust analysis of all major religious groups in India – Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains – as well as all major regional zones. Data was weighted to account for the different probabilities of selection among respondents and to align with demographic benchmarks for the Indian adult population from the 2011 census. The survey is calculated to have covered 98% of Indians ages 18 and older and had an 86% national response rate.

For more information, see the Methodology for this report. The questions used in this analysis can be found here.

More than 70 years after India became free from colonial rule, Indians generally feel their country has lived up to one of its post-independence ideals: a society where followers of many religions can live and practice freely.

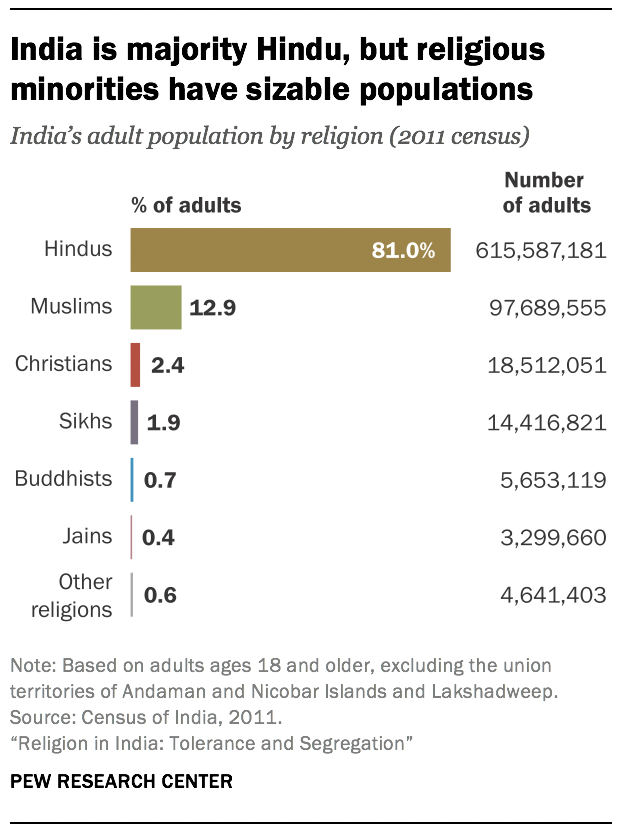

India’s massive population is diverse as well as devout. Not only do most of the world’s Hindus, Jains and Sikhs live in India, but it also is home to one of the world’s largest Muslim populations and to millions of Christians and Buddhists.

A major new Pew Research Center survey of religion across India, based on nearly 30,000 face-to-face interviews of adults conducted in 17 languages between late 2019 and early 2020 (before the COVID-19 pandemic), finds that Indians of all these religious backgrounds overwhelmingly say they are very free to practice their faiths.

Related India research

This is one in a series of Pew Research Center reports on India based on a survey of 29,999 Indian adults conducted Nov. 17, 2019, to March 23, 2020, as well as demographic data from the Indian Census and other government sources. Other reports can be found here:

- How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society

- Religious Composition of India

- India’s Sex Ratio at Birth Begins To Normalize

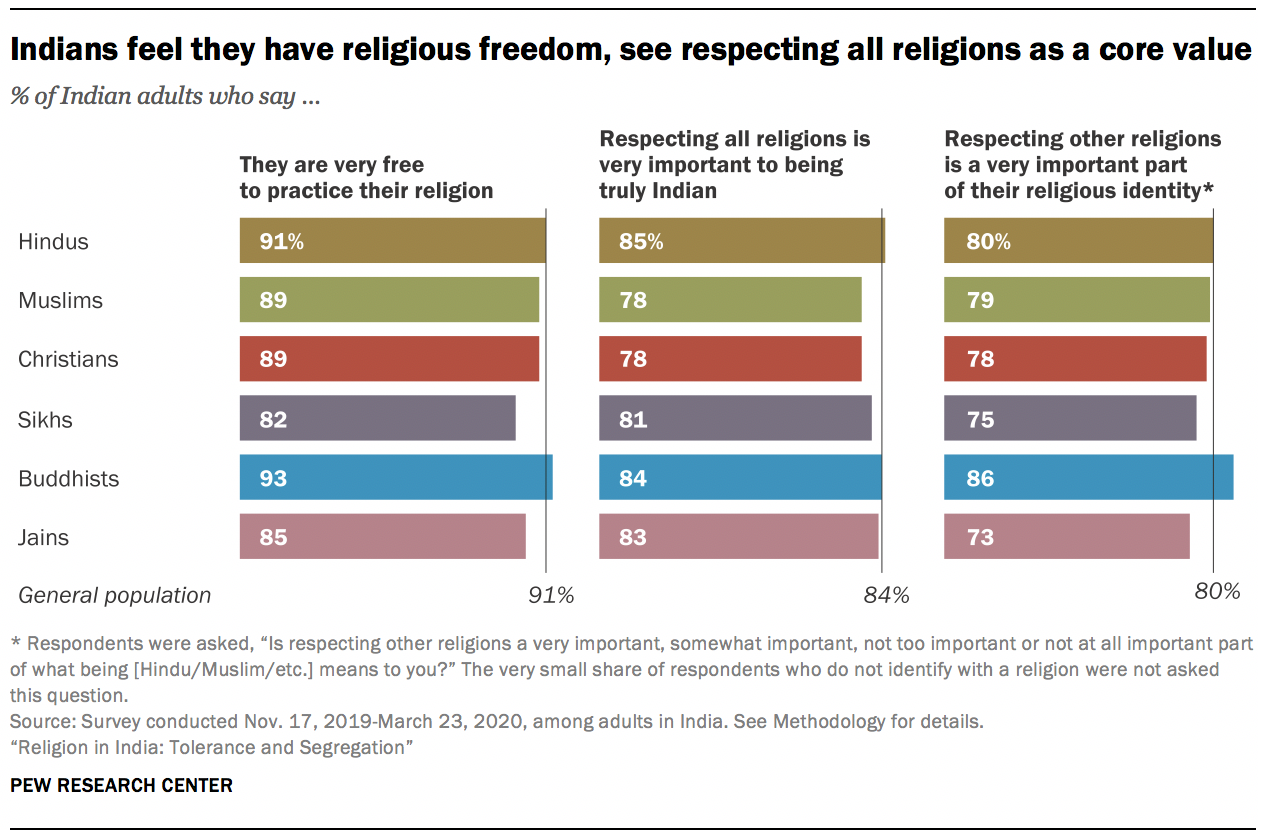

Indians see religious tolerance as a central part of who they are as a nation. Across the major religious groups, most people say it is very important to respect all religions to be “truly Indian.” And tolerance is a religious as well as civic value: Indians are united in the view that respecting other religions is a very important part of what it means to be a member of their own religious community.

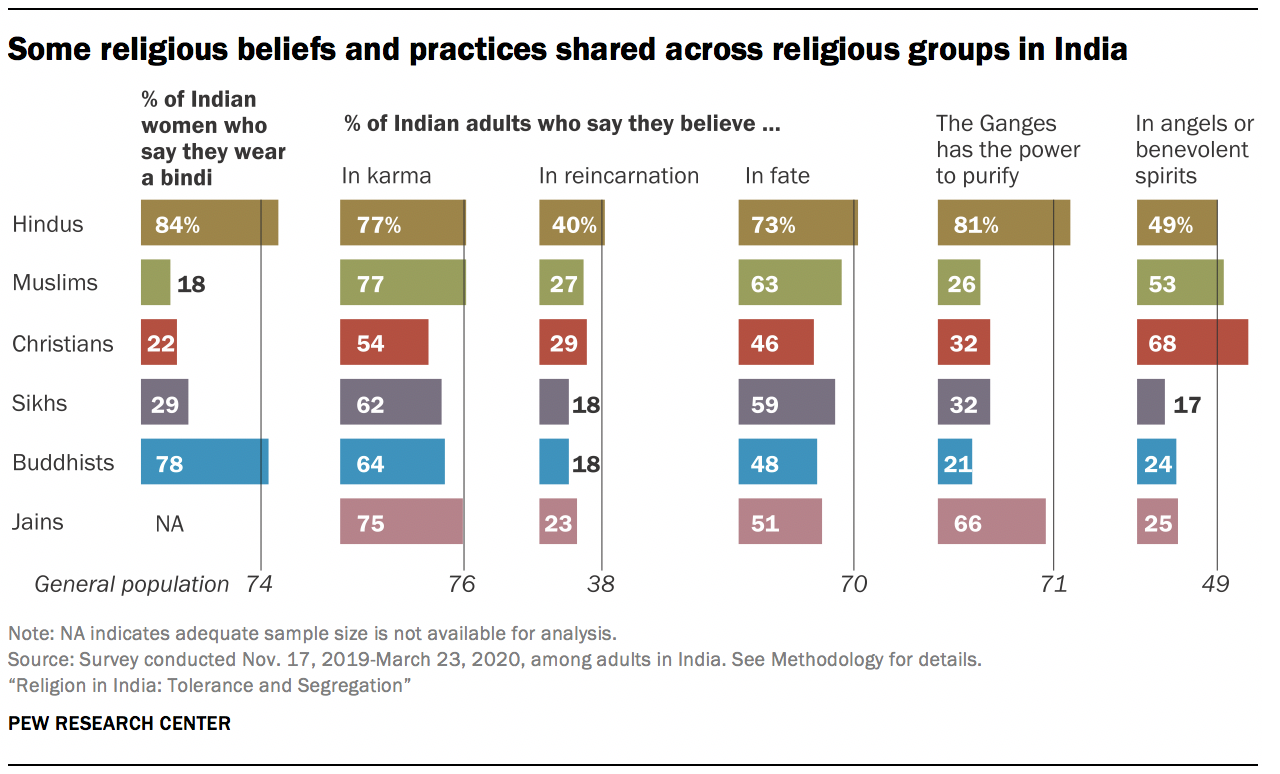

These shared values are accompanied by a number of beliefs that cross religious lines. Not only do a majority of Hindus in India (77%) believe in karma, but an identical percentage of Muslims do, too. A third of Christians in India (32%) – together with 81% of Hindus – say they believe in the purifying power of the Ganges River, a central belief in Hinduism. In Northern India, 12% of Hindus and 10% of Sikhs, along with 37% of Muslims, identity with Sufism, a mystical tradition most closely associated with Islam. And the vast majority of Indians of all major religious backgrounds say that respecting elders is very important to their faith.

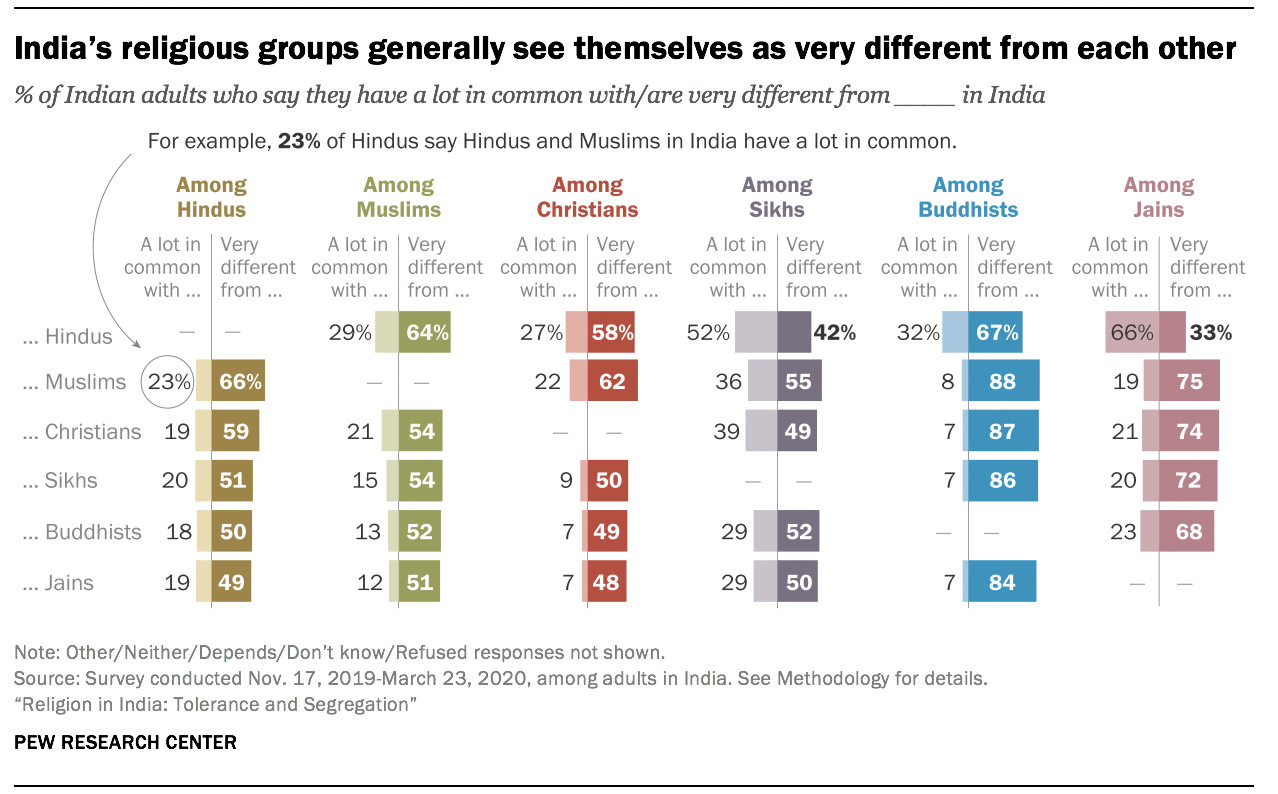

Yet, despite sharing certain values and religious beliefs – as well as living in the same country, under the same constitution – members of India’s major religious communities often don’t feel they have much in common with one another. The majority of Hindus see themselves as very different from Muslims (66%), and most Muslims return the sentiment, saying they are very different from Hindus (64%). There are a few exceptions: Two-thirds of Jains and about half of Sikhs say they have a lot in common with Hindus. But generally, people in India’s major religious communities tend to see themselves as very different from others.

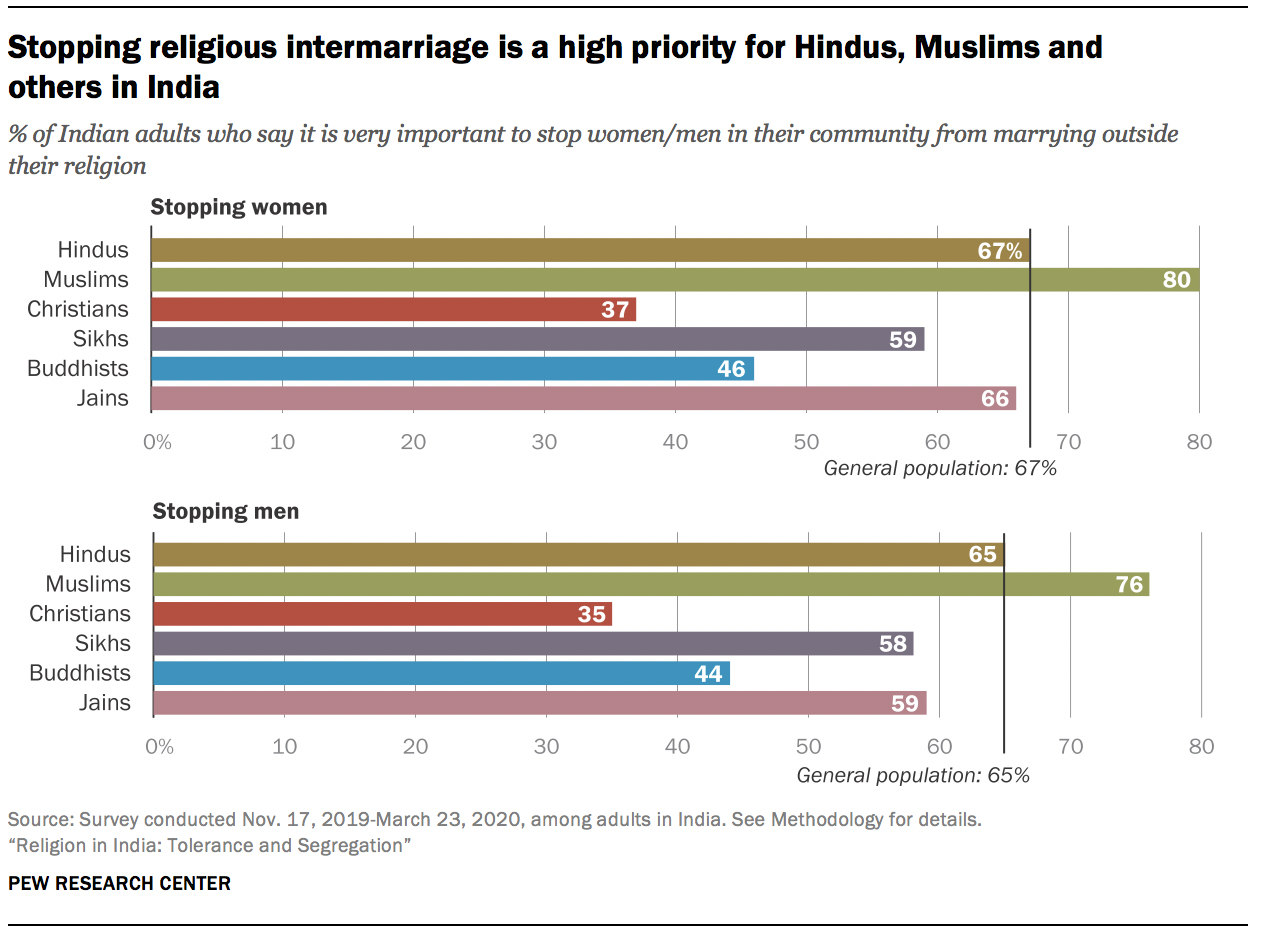

This perception of difference is reflected in traditions and habits that maintain the separation of India’s religious groups. For example, marriages across religious lines – and, relatedly, religious conversions – are exceedingly rare (see Chapter 3). Many Indians, across a range of religious groups, say it is very important to stop people in their community from marrying into other religious groups. Roughly two-thirds of Hindus in India want to prevent interreligious marriages of Hindu women (67%) or Hindu men (65%). Even larger shares of Muslims feel similarly: 80% say it is very important to stop Muslim women from marrying outside their religion, and 76% say it is very important to stop Muslim men from doing so.

Moreover, Indians generally stick to their own religious group when it comes to their friends. Hindus overwhelmingly say that most or all of their close friends are also Hindu. Of course, Hindus make up the majority of the population, and as a result of sheer numbers, may be more likely to interact with fellow Hindus than with people of other religions. But even among Sikhs and Jains, who each form a sliver of the national population, a large majority say their friends come mainly or entirely from their small religious community.

Fewer Indians go so far as to say that their neighborhoods should consist only of people from their own religious group. Still, many would prefer to keep people of certain religions out of their residential areas or villages. For example, many Hindus (45%) say they are fine with having neighbors of all other religions – be they Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain – but an identical share (45%) say they would not be willing to accept followers of at least one of these groups, including more than one-in-three Hindus (36%) who do not want a Muslim as a neighbor. Among Jains, a majority (61%) say they are unwilling to have neighbors from at least one of these groups, including 54% who would not accept a Muslim neighbor, although nearly all Jains (92%) say they would be willing to accept a Hindu neighbor.

Indians, then, simultaneously express enthusiasm for religious tolerance and a consistent preference for keeping their religious communities in segregated spheres – they live together separately. These two sentiments may seem paradoxical, but for many Indians they are not.

Indeed, many take both positions, saying it is important to be tolerant of others and expressing a desire to limit personal connections across religious lines. Indians who favor a religiously segregated society also overwhelmingly emphasize religious tolerance as a core value. For example, among Hindus who say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of Hindu women, 82% also say that respecting other religions is very important to what it means to be Hindu. This figure is nearly identical to the 85% who strongly value religious tolerance among those who are not at all concerned with stopping interreligious marriage.

In other words, Indians’ concept of religious tolerance does not necessarily involve the mixing of religious communities. While people in some countries may aspire to create a “melting pot” of different religious identities, many Indians seem to prefer a country more like a patchwork fabric, with clear lines between groups.

The dimensions of Hindu nationalism in India

One of these religious fault lines – the relationship between India’s Hindu majority and the country’s smaller religious communities – has particular relevance in public life, especially in recent years under the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the BJP is often described as promoting a Hindu nationalist ideology.

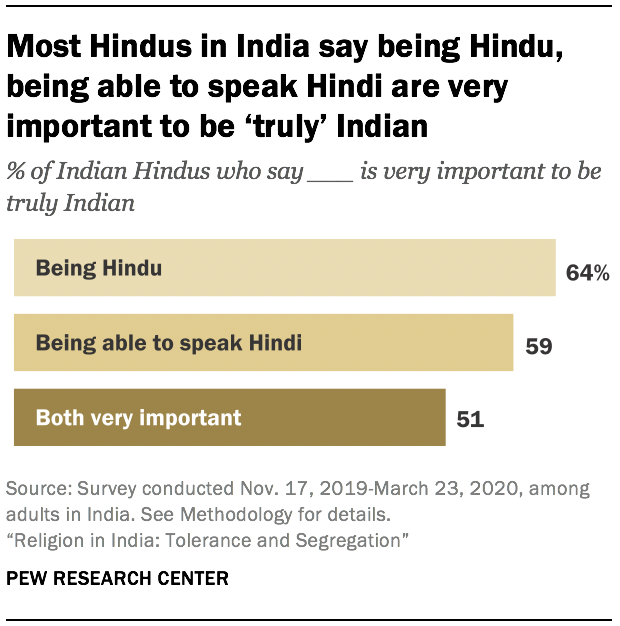

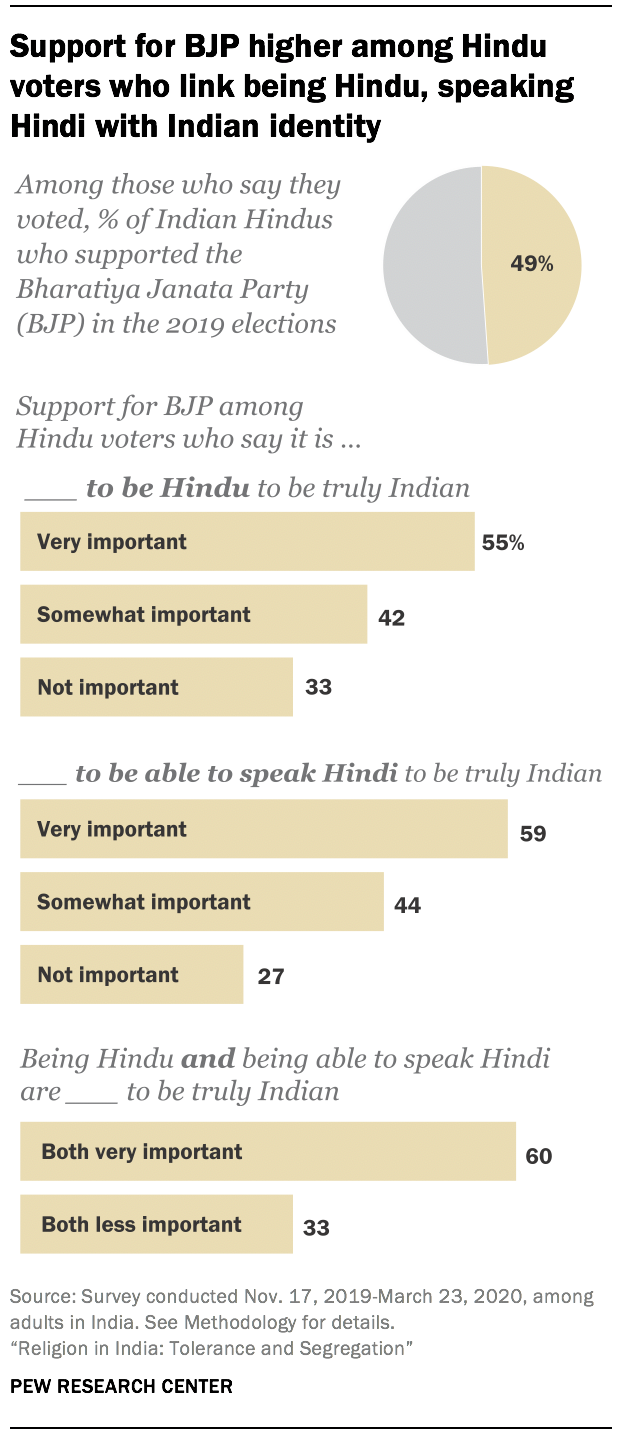

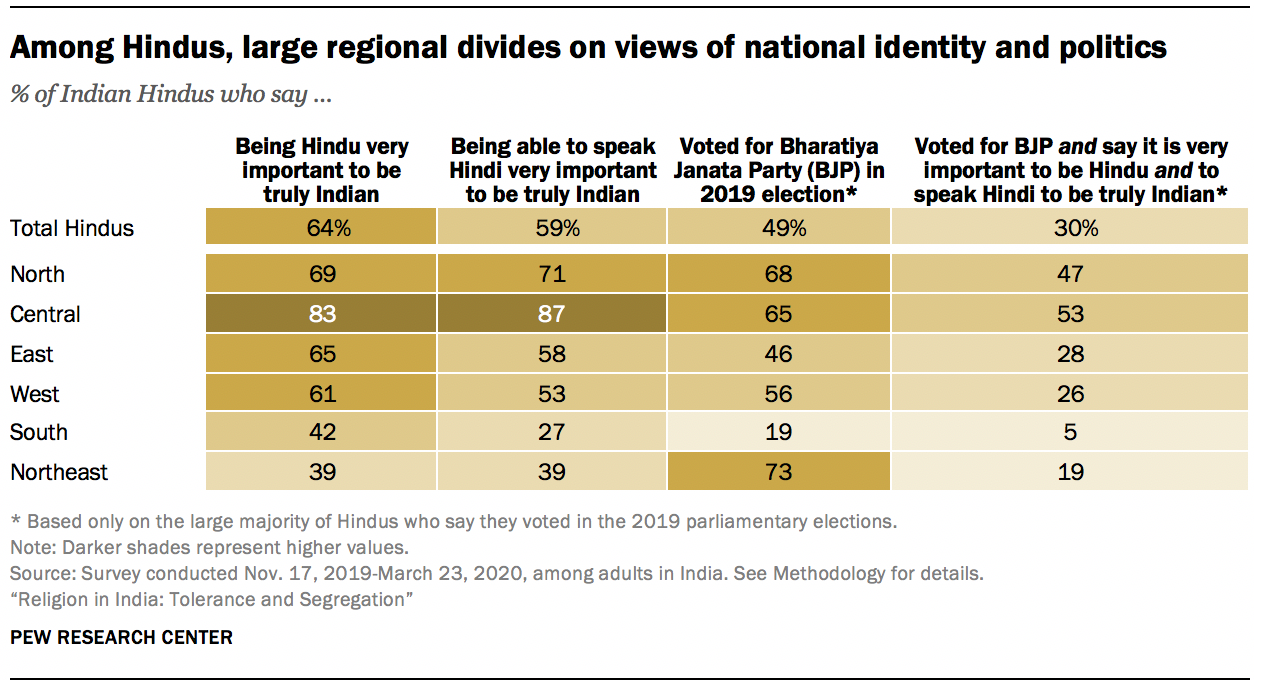

The survey finds that Hindus tend to see their religious identity and Indian national identity as closely intertwined: Nearly two-thirds of Hindus (64%) say it is very important to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian.

Most Hindus (59%) also link Indian identity with being able to speak Hindi – one of dozens of languages that are widely spoken in India. And these two dimensions of national identity – being able to speak Hindi and being a Hindu – are closely connected. Among Hindus who say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, fully 80% also say it is very important to speak Hindi to be truly Indian.

The BJP’s appeal is greater among Hindus who closely associate their religious identity and the Hindi language with being “truly Indian.” In the 2019 national elections, 60% of Hindu voters who think it is very important to be Hindu and to speak Hindi to be truly Indian cast their vote for the BJP, compared with only a third among Hindu voters who feel less strongly about both these aspects of national identity.

Overall, among those who voted in the 2019 elections, three-in-ten Hindus take all three positions: saying it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian; saying the same about speaking Hindi; and casting their ballot for the BJP.

These views are considerably more common among Hindus in the largely Hindi-speaking Northern and Central regions of the country, where roughly half of all Hindu voters fall into this category, compared with just 5% in the South.

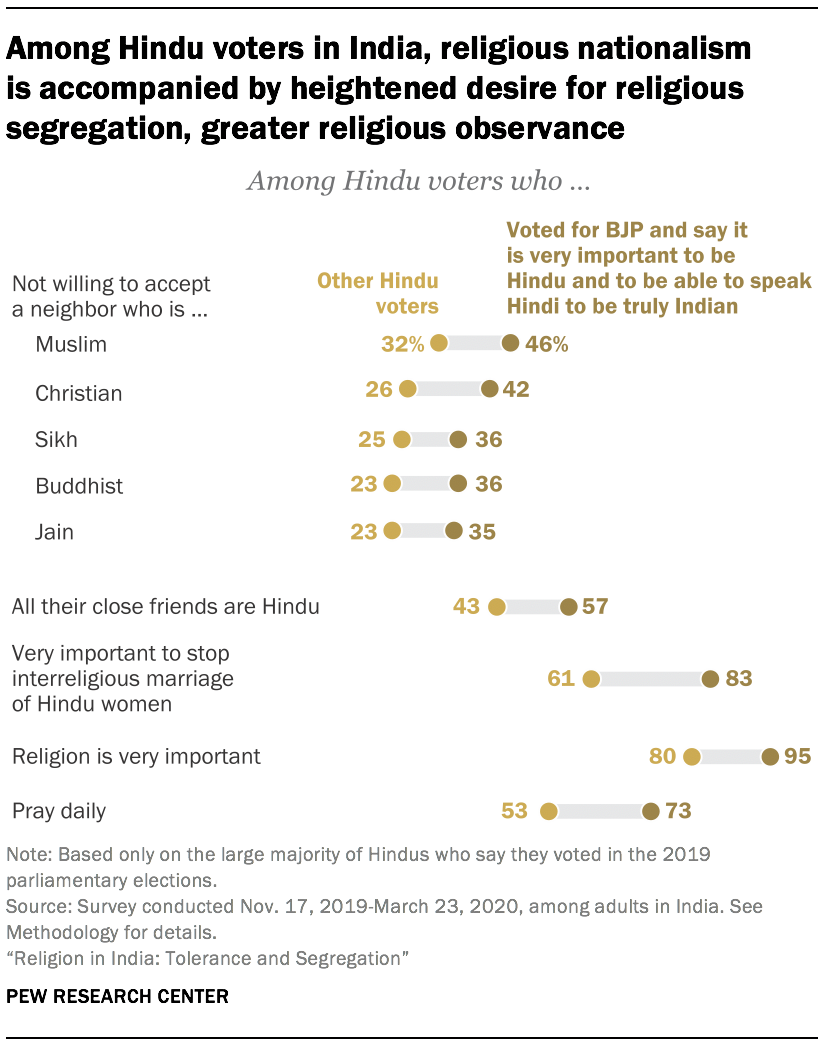

Whether Hindus who meet all three of these criteria qualify as “Hindu nationalists” may be debated, but they do express a heightened desire for maintaining clear lines between Hindus and other religious groups when it comes to whom they marry, who their friends are and whom they live among. For example, among Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with both religion and language, 83% say it is very important to stop Hindu women from marrying into another religion, compared with 61% among other Hindu voters.

This group also tends to be more religiously observant: 95% say religion is very important in their lives, and roughly three-quarters say they pray daily (73%). By comparison, among other Hindu voters, a smaller majority (80%) say religion is very important in their lives, and about half (53%) pray daily.

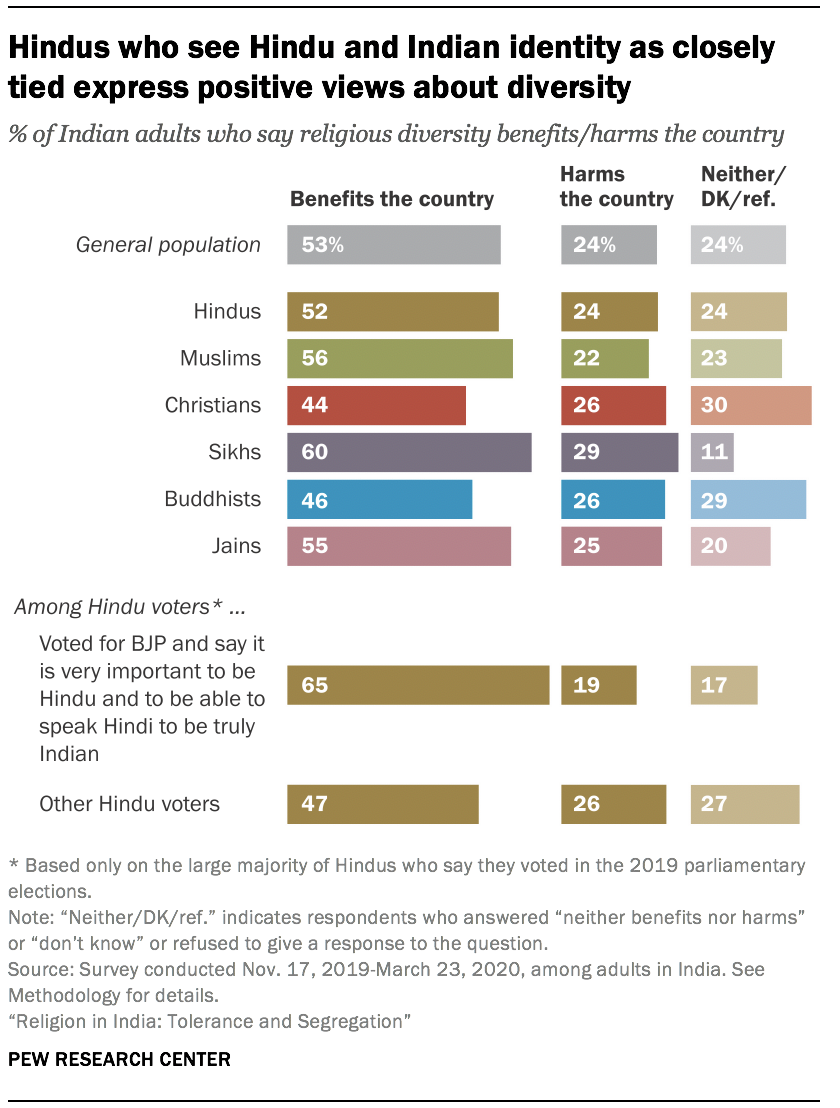

Even though Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with religion and language are more inclined to support a religiously segregated India, they also are more likely than other Hindu voters to express positive opinions about India’s religious diversity. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of this group – Hindus who say that being a Hindu and being able to speak Hindi are very important to be truly Indian and who voted for the BJP in 2019 – say religious diversity benefits India, compared with about half (47%) of other Hindu voters.

This finding suggests that for many Hindus, there is no contradiction between valuing religious diversity (at least in principle) and feeling that Hindus are somehow more authentically Indian than fellow citizens who follow other religions.

Among Indians overall, there is no overwhelming consensus on the benefits of religious diversity. On balance, more Indians see diversity as a benefit than view it as a liability for their country: Roughly half (53%) of Indian adults say India’s religious diversity benefits the country, while about a quarter (24%) see diversity as harmful, with similar figures among both Hindus and Muslims. But 24% of Indians do not take a clear position either way – they say diversity neither benefits nor harms the country, or they decline to answer the question. (See Chapter 2 for a discussion of attitudes toward diversity.)

India’s Muslims express pride in being Indian while identifying communal tensions, desiring segregation

India’s Muslim community, the second-largest religious group in the country, historically has had a complicated relationship with the Hindu majority. The two communities generally have lived peacefully side by side for centuries, but their shared history also is checkered by civil unrest and violence. Most recently, while the survey was being conducted, demonstrations broke out in parts of New Delhi and elsewhere over the government’s new citizenship law, which creates an expedited path to citizenship for immigrants from some neighboring countries – but not Muslims.

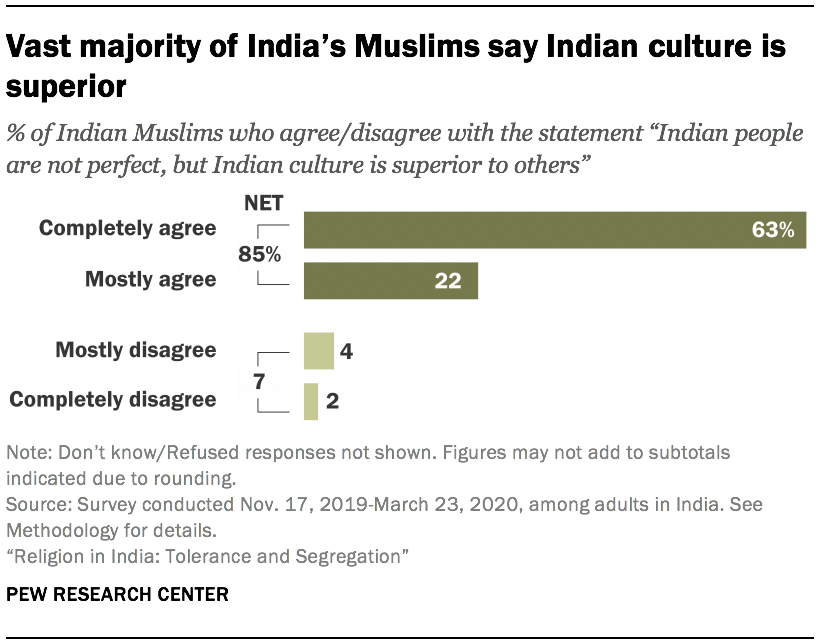

Today, India’s Muslims almost unanimously say they are very proud to be Indian (95%), and they express great enthusiasm for Indian culture: 85% agree with the statement that “Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others.”

Relatively few Muslims say their community faces “a lot” of discrimination in India (24%). In fact, the share of Muslims who see widespread discrimination against their community is similar to the share of Hindus who say Hindus face widespread religious discrimination in India (21%). (See Chapter 1 for a discussion of attitudes on religious discrimination.)

But personal experiences with discrimination among Muslims vary quite a bit regionally. Among Muslims in the North, 40% say they personally have faced religious discrimination in the last 12 months – much higher levels than reported in most other regions.

In addition, most Muslims across the country (65%), along with an identical share of Hindus (65%), see communal violence as a very big national problem. (See Chapter 1 for a discussion of Indians’ attitudes toward national problems.)

Like Hindus, Muslims prefer to live religiously segregated lives – not just when it comes to marriage and friendships, but also in some elements of public life. In particular, three-quarters of Muslims in India (74%) support having access to the existing system of Islamic courts, which handle family disputes (such as inheritance or divorce cases), in addition to the secular court system.

Muslims’ desire for religious segregation does not preclude tolerance of other groups – again similar to the pattern seen among Hindus. Indeed, a majority of Muslims who favor separate religious courts for their community say religious diversity benefits India (59%), compared with somewhat fewer of those who oppose religious courts for Muslims (50%).

Sidebar: Islamic courts in India

Since 1937, India’s Muslims have had the option of resolving family and inheritance-related cases in officially recognized Islamic courts, known as dar-ul-qaza. These courts are overseen by religious magistrates known as qazi and operate under Shariah principles. For example, while the rules of inheritance for most Indians are governed by the Indian Succession Act of 1925 and the Hindu Succession Act of 1956 (amended in 2005), Islamic inheritance practices differ in some ways, including who can be considered an heir and how much of the deceased person’s property they can inherit. India’s inheritance laws also take into account the differing traditions of other religious communities, such as Hindus and Christians, but their cases are handled in secular courts. Only the Muslim community has the option of having cases tried by a separate system of family courts. The decisions of the religious courts, however, are not legally binding, and the parties involved have the option of taking their case to secular courts if they are not satisfied with the decision of the religious court.

As of 2021, there are roughly 70 dar-ul-qaza in India. Most are in the states of Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. Goa is the only state that does not recognize rulings by these courts, enforcing its own uniform civil code instead. Dar-ul-qaza are overseen by the All India Muslim Personal Law Board.

While these courts can grant divorces among Muslims, they are prohibited from approving divorces initiated through the practice known as triple talaq, in which a Muslim man instantly divorces his wife by saying the Arabic/Urdu word “talaq” (meaning “divorce”) three times. This practice was deemed unconstitutional by the Indian Supreme Court in 2017 and formally outlawed by the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s Parliament, in 2019. 1

Recent debates have emerged around Islamic courts. Some Indians have expressed concern that the rise of dar-ul-qaza could undermine the Indian judiciary, because a subset of the population is not bound to the same laws as everyone else. Others have argued that the rulings of Islamic courts are particularly unfair to women, although the prohibition of triple talaq may temper some of these criticisms. In its 2019 political manifesto, the BJP proclaimed a desire to create a national Uniform Civil Code, saying it would increase gender equality.

Some Indian commentators have voiced opposition to Islamic courts along with more broadly negative sentiments against Muslims, describing the rising numbers of dar-ul-qaza as the “Talibanization” of India, for example.

On the other hand, Muslim scholars have defended the dar-ul-qaza, saying they expedite justice because family disputes that would otherwise clog India’s courts can be handled separately, allowing the secular courts to focus their attention on other concerns.

Since 2018, the Hindu nationalist party Hindu Mahasabha (which does not hold any seats in Parliament) has tried to set up Hindu religious courts, known as Hindutva courts, aiming to play a role similar to dar-ul-qaza, only for the majority Hindu community. None of these courts have been recognized by the Indian government, and their rulings are not considered legally binding.

Muslims, Hindus diverge over legacy of Partition

The seminal event in the modern history of Hindu-Muslim relations in the region was the partition of the subcontinent into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan at the end of the British colonial period in 1947. Partition remains one of the largest movements of people across borders in recorded history, and in both countries the carving of new borders was accompanied by violence, rioting and looting.

More than seven decades later, the predominant view among Indian Muslims is that the partition of the subcontinent was “a bad thing” for Hindu-Muslim relations. Nearly half of Muslims say Partition hurt communal relations with Hindus (48%), while fewer say it was a good thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (30%). Among Muslims who prefer more religious segregation – that is, who say they would not accept a person of a different faith as a neighbor – an even higher share (60%) say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations.

Sikhs, whose homeland of Punjab was split by Partition, are even more likely than Muslims to say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations: Two-thirds of Sikhs (66%) take this position. And Sikhs ages 60 and older, whose parents most likely lived through Partition, are more inclined than younger Sikhs to say the partition of the country was bad for communal relations (74% vs. 64%).

While Sikhs and Muslims are more likely to say Partition was a bad thing than a good thing, Hindus lean in the opposite direction: 43% of Hindus say Partition was beneficial for Hindu-Muslim relations, while 37% see it as a bad thing.

Context for the survey

Interviews were conducted after the conclusion of the 2019 national parliamentary elections and after the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status under the Indian Constitution. In December 2019, protests against the country’s new citizenship law broke out in several regions.

Fieldwork could not be conducted in the Kashmir Valley and a few districts elsewhere due to security concerns. These locations include some heavily Muslim areas, which is part of the reason why Muslims make up 11% of the survey’s total sample, while India’s adult population is roughly 13% Muslim, according to the most recent census data that is publicly available, from 2011. In addition, it is possible that in some other parts of the country, interreligious tensions over the new citizenship law may have slightly depressed participation in the survey by potential Muslim respondents.

Nevertheless, the survey’s estimates of religious beliefs, behaviors and attitudes can be reported with a high degree of confidence for India’s total population, because the number of people living in the excluded areas (Manipur, Sikkim, the Kashmir Valley and a few other districts) is not large enough to affect the overall results at the national level. About 98% of India’s total population had a chance of being selected for this survey.

Greater caution is warranted when looking at India’s Muslims separately, as a distinct population. The survey cannot speak to the experiences and views of Kashmiri Muslims. Still, the survey does represent the beliefs, behaviors and attitudes of around 95% of India’s overall Muslim population.

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted face-to-face nationally among 29,999 Indian adults. Local interviewers administered the survey between Nov. 17, 2019, and March 23, 2020, in 17 languages. The survey covered all states and union territories of India, with the exceptions of Manipur and Sikkim, where the rapidly developing COVID-19 situation prevented fieldwork from starting in the spring of 2020, and the remote territories of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep; these areas are home to about a quarter of 1% of the Indian population. The union territory of Jammu and Kashmir was covered by the survey, though no fieldwork was conducted in the Kashmir region itself due to security concerns.

This study, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of a larger effort by Pew Research Center to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many other countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America; Israel; Central and Eastern Europe; Western Europe; and the United States.

The rest of this Overview covers attitudes on five broad topics: caste and discrimination; religious conversion; religious observances and beliefs; how people define their religious identity, including what kind of behavior is considered acceptable to be a Hindu or a Muslim; and the connection between economic development and religious observance.

Caste is another dividing line in Indian society, and not just among Hindus

Religion is not the only fault line in Indian society. In some regions of the country, significant shares of people perceive widespread, caste-based discrimination.

The caste system is an ancient social hierarchy based on occupation and economic status. People are born into a particular caste and tend to keep many aspects of their social life within its boundaries, including whom they marry. Even though the system’s origins are in historical Hindu writings, today Indians nearly universally identify with a caste, regardless of whether they are Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain.

Overall, the majority of Indian adults say they are a member of a Scheduled Caste (SC) – often referred to as Dalits (25%) – Scheduled Tribe (ST) (9%) or Other Backward Class (OBC) (35%). 2

Buddhists in India nearly universally identify themselves in these categories, including 89% who are Dalits (sometimes referred to by the pejorative term “untouchables”).

Members of SC/ST/OBC groups traditionally formed the lower social and economic rungs of Indian society, and historically they have faced discrimination and unequal economic opportunities. The practice of untouchability in India ostracizes members of many of these communities, especially Dalits, although the Indian Constitution prohibits caste-based discrimination, including untouchability, and in recent decades the government has enacted economic advancement policies like reserved seats in universities and government jobs for Dalits, Scheduled Tribes and OBC communities.

Roughly 30% of Indians do not belong to these protected groups and are classified as “General Category.” This includes higher castes such as Brahmins (4%), traditionally the priestly caste. Indeed, each broad category includes several sub-castes – sometimes hundreds – with their own social and economic hierarchies.

Three-quarters of Jains (76%) identify with General Category castes, as do 46% of both Muslims and Sikhs.

Caste-based discrimination, as well as the government’s efforts to compensate for past discrimination, are politically charged topics in India. But the survey finds that most Indians do not perceive widespread caste-based discrimination. Just one-in-five Indians say there is a lot of discrimination against members of SCs, while 19% say there is a lot of discrimination against STs and somewhat fewer (16%) see high levels of discrimination against OBCs. Members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are slightly more likely than others to perceive widespread discrimination against their two groups. Still, large majorities of people in these categories do not think they face a lot of discrimination.

These attitudes vary by region, however. Among Southern Indians, for example, 30% see widespread discrimination against Dalits, compared with 13% in the Central part of the country. And among the Dalit community in the South, even more (43%) say their community faces a lot of discrimination, compared with 27% among Southern Indians in the General Category who say the Dalit community faces widespread discrimination in India.

A higher share of Dalits in the South and Northeast than elsewhere in the country say they, personally, have faced discrimination in the last 12 months because of their caste: 30% of Dalits in the South say this, as do 38% in the Northeast.

Although caste discrimination may not be perceived as widespread nationally, caste remains a potent factor in Indian society. Most Indians from other castes say they would be willing to have someone belonging to a Scheduled Caste as a neighbor (72%). But a similarly large majority of Indians overall (70%) say that most or all of their close friends share their caste. And Indians tend to object to marriages across caste lines, much as they object to interreligious marriages. 3

Overall, 64% of Indians say it is very important to stop women in their community from marrying into other castes, and about the same share (62%) say it is very important to stop men in their community from marrying into other castes. These figures vary only modestly across members of different castes. For example, nearly identical shares of Dalits and members of General Category castes say stopping inter-caste marriages is very important.

Majorities of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains consider stopping inter-caste marriage of both men and women a high priority. By comparison, fewer Buddhists and Christians say it is very important to stop such marriages – although for majorities of both groups, stopping people from marrying outside their caste is at least “somewhat” important.

People surveyed in India’s South and Northeast see greater caste discrimination in their communities, and they also raise fewer objections to inter-caste marriages than do Indians overall. Meanwhile, college-educated Indians are less likely than those with less education to say stopping inter-caste marriages is a high priority. But, even within the most highly educated group, roughly half say preventing such marriages is very important. (See Chapter 4 for more analysis of Indians’ views on caste.)

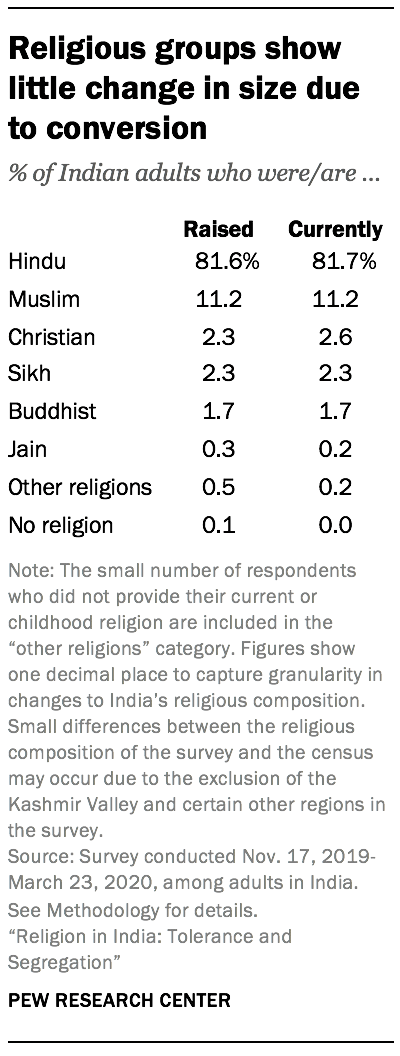

Religious conversion in India

In recent years, conversion of people belonging to lower castes (including Dalits) away from Hinduism – a traditionally non-proselytizing religion – to proselytizing religions, especially Christianity, has been a contentious political issue in India. As of early 2021, nine states have enacted laws against proselytism, and some previous surveys have shown that half of Indians support legal bans on religious conversions. 4

This survey, though, finds that religious switching, or conversion, has a minimal impact on the overall size of India’s religious groups. For example, according to the survey, 82% of Indians say they were raised Hindu, and a nearly identical share say they are currently Hindu, showing no net losses for the group through conversion to other religions. Other groups display similar levels of stability.

Changes in India’s religious landscape over time are largely a result of differences in fertility rates among religious groups, not conversion.

Respondents were asked two separate questions to measure religious switching: “What is your present religion, if any?” and, later in the survey, “In what religion were you raised, if any?” Overall, 98% of respondents give the same answer to both these questions.

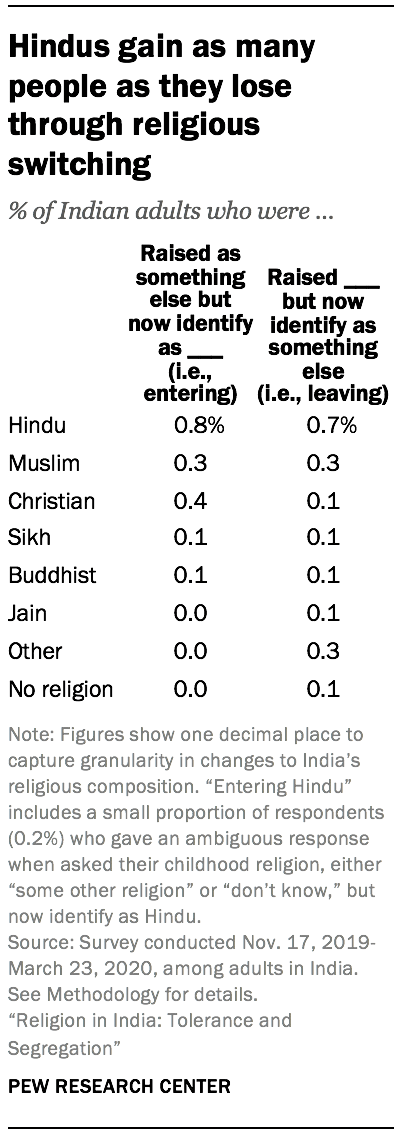

An overall pattern of stability in the share of religious groups is accompanied by little net gain from movement into, or out of, most religious groups. Among Hindus, for instance, any conversion out of the group is matched by conversion into the group: 0.7% of respondents say they were raised Hindu but now identify as something else, and although Hindu texts and traditions do not agree on any formal process for conversion into the religion, roughly the same share (0.8%) say they were not raised Hindu but now identify as Hindu. 5 Most of these new followers of Hinduism are married to Hindus.

Similarly, 0.3% of respondents have left Islam since childhood, matched by an identical share who say they were raised in other religions (or had no childhood religion) and have since become Muslim.

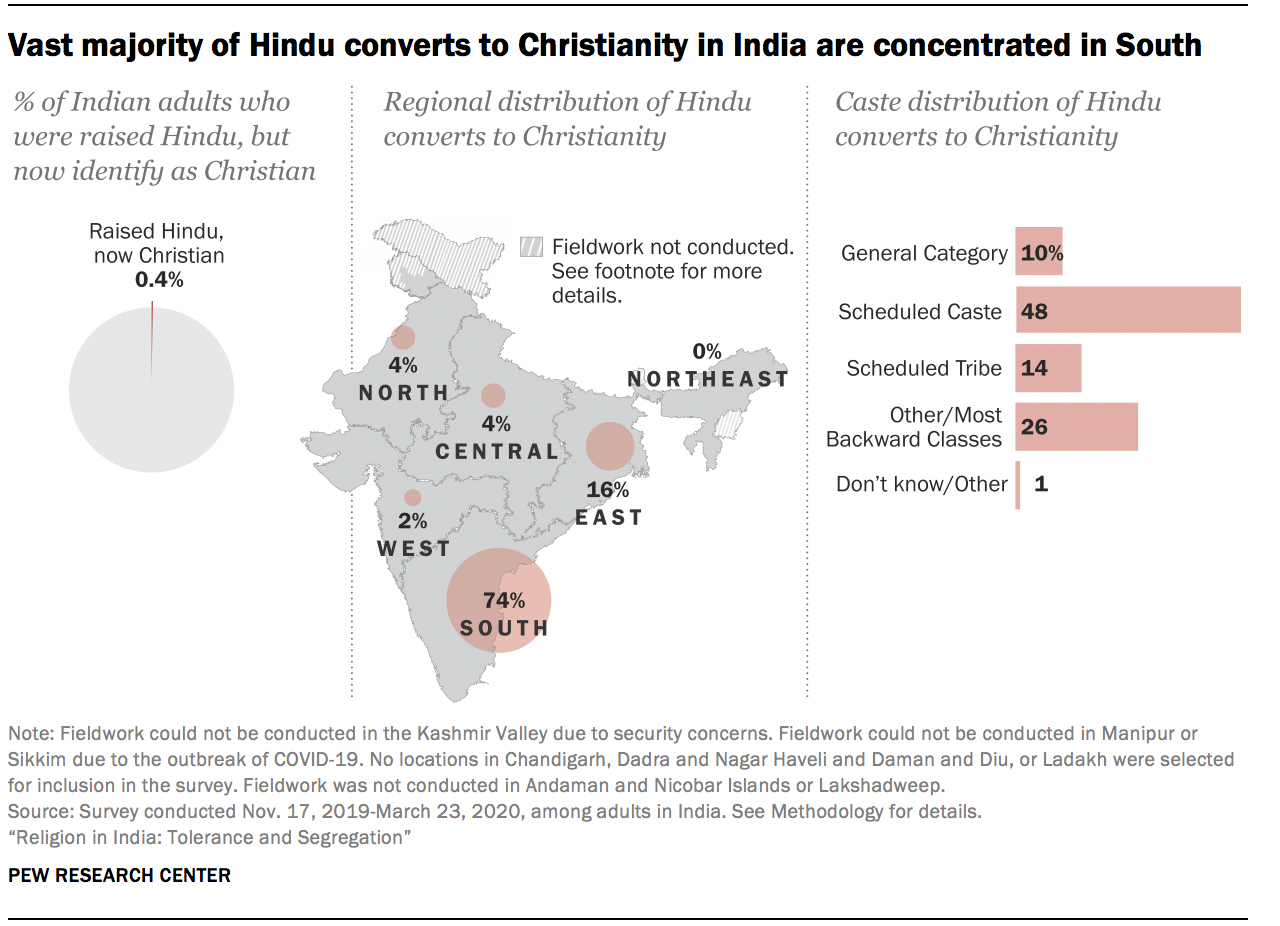

For Christians, however, there are some net gains from conversion: 0.4% of survey respondents are former Hindus who now identify as Christian, while 0.1% are former Christians.

Three-quarters of India’s Hindu converts to Christianity (74%) are concentrated in the Southern part of the country – the region with the largest Christian population. As a result, the Christian population of the South shows a slight increase within the lifetime of survey respondents: 6% of Southern Indians say they were raised Christian, while 7% say they are currently Christian.

Some Christian converts (16%) reside in the East as well (the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal); about two-thirds of all Christians in the East (64%) belong to Scheduled Tribes.

Nationally, the vast majority of former Hindus who are now Christian belong to Scheduled Castes (48%), Scheduled Tribes (14%) or Other Backward Classes (26%). And former Hindus are much more likely than the Indian population overall to say there is a lot of discrimination against lower castes in India. For example, nearly half of converts to Christianity (47%) say there is a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes in India, compared with 20% of the overall population who perceive this level of discrimination against Scheduled Castes. Still, relatively few converts say they, personally, have faced discrimination due to their caste in the last 12 months (12%).

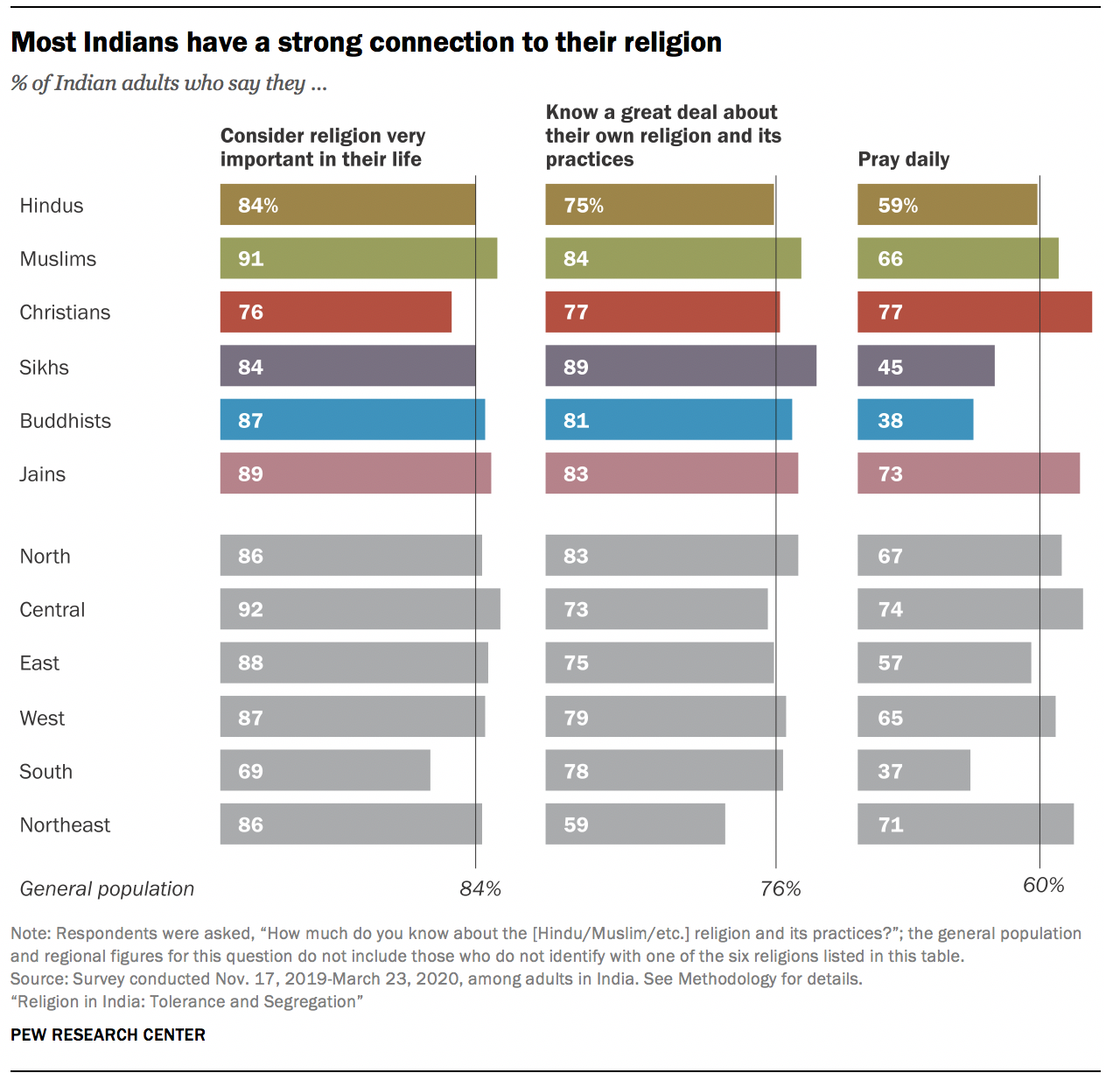

Religion very important across India’s religious groups

Though their specific practices and beliefs may vary, all of India’s major religious communities are highly observant by standard measures. For instance, the vast majority of Indians, across all major faiths, say that religion is very important in their lives. And at least three-quarters of each major religion’s followers say they know a great deal about their own religion and its practices. For example, 81% of Indian Buddhists claim a great deal of knowledge about the Buddhist religion and its practices.

Indian Muslims are slightly more likely than Hindus to consider religion very important in their lives (91% vs. 84%). Muslims also are modestly more likely than Hindus to say they know a great deal about their own religion (84% vs. 75%).

Significant portions of each religious group also pray daily, with Christians among the most likely to do so (77%) – even though Christians are the least likely of the six groups to say religion is very important in their lives (76%). Most Hindus and Jains also pray daily (59% and 73%, respectively) and say they perform puja daily (57% and 81%), either at home or at a temple. 6

Generally, younger and older Indians, those with different educational backgrounds, and men and women are similar in their levels of religious observance. South Indians are the least likely to say religion is very important in their lives (69%), and the South is the only region where fewer than half of people report praying daily (37%). While Hindus, Muslims and Christians in the South are all less likely than their counterparts elsewhere in India to say religion is very important to them, the lower rate of prayer in the South is driven mainly by Hindus: Three-in-ten Southern Hindus report that they pray daily (30%), compared with roughly two-thirds (68%) of Hindus in the rest of the country (see “People in the South differ from rest of the country in their views of religion, national identity” below for further discussion of religious differences in Southern India).

The survey also asked about three rites of passage: religious ceremonies for birth (or infancy), marriage and death. Members of all of India’s major religious communities tend to see these rites as highly important. For example, the vast majority of Muslims (92%), Christians (86%) and Hindus (85%) say it is very important to have a religious burial or cremation for their loved ones.

The survey also asked about practices specific to particular religions, such as whether people have received purification by bathing in holy bodies of water, like the Ganges River, a rite closely associated with Hinduism. About two-thirds of Hindus have done this (65%). Most Hindus also have holy basil (the tulsi plant) in their homes, as do most Jains (72% and 62%, respectively). And about three-quarters of Sikhs follow the Sikh practice of keeping their hair long (76%).

For more on religious practices across India’s religious groups, see Chapter 7.

Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived

Nearly all Indians say they believe in God (97%), and roughly 80% of people in most religious groups say they are absolutely certain that God exists. The main exception is Buddhists, one-third of whom say they do not believe in God. Still, among Buddhists who do think there is a God, most say they are absolutely certain in this belief.

While belief in God is close to universal in India, the survey finds a wide range of views about the type of deity or deities that Indians believe in. The prevailing view is that there is one God “with many manifestations” (54%). But about one-third of the public says simply: “There is only one God” (35%). Far fewer say there are many gods (6%).

Even though Hinduism is sometimes referred to as a polytheistic religion, very few Hindus (7%) take the position that there are multiple gods. Instead, the most common position among Hindus (as well as among Jains) is that there is “only one God with many manifestations” (61% among Hindus and 54% among Jains).

Among Hindus, those who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than other Hindus to believe in one God with many manifestations (63% vs. 50%) and less likely to say there are many gods (6% vs. 12%).

By contrast, majorities of Muslims, Christians and Sikhs say there is only one God. And among Buddhists, the most common response is also a belief in one God. Among all these groups, however, about one-in-five or more say God has many manifestations, a position closer to their Hindu compatriots’ concept of God.

Most Hindus feel close to multiple gods, but Shiva, Hanuman and Ganesha are most popular

Traditionally, many Hindus have a “personal god,” or ishta devata: A particular god or goddess with whom they feel a personal connection. The survey asked all Indian Hindus who say they believe in God which god they feel closest to – showing them 15 images of gods on a card as possible options – and the vast majority of Hindus selected more than one god or indicated that they have many personal gods (84%). 7 This is true not only among Hindus who say they believe in many gods (90%) or in one God with many manifestations (87%), but also among those who say there is only one God (82%).

The god that Hindus most commonly feel close to is Shiva (44%). In addition, about one-third of Hindus feel close to Hanuman or Ganesha (35% and 32%, respectively).

There is great regional variation in how close India’s Hindus feel to some gods. For example, 46% of Hindus in India’s West feel close to Ganesha, but only 15% feel this way in the Northeast. And 46% of Hindus in the Northeast feel close to Krishna, while just 14% in the South say the same.

Feelings of closeness for Lord Ram are especially strong in the Central region (27%), which includes what Hindus claim is his ancient birthplace, Ayodhya. The location in Ayodhya where many Hindus believe Ram was born has been a source of controversy: Hindu mobs demolished a mosque on the site in 1992, claiming that a Hindu temple originally existed there. In 2019, the Indian Supreme Court ruled that the demolished mosque had been built on top of a preexisting non-Islamic structure and that the land should be given to Hindus to build a temple, with another location in the area given to the Muslim community to build a new mosque. (For additional findings on belief in God, see Chapter 12.)

Sidebar: Despite economic advancement, few signs that importance of religion is declining

A prominent theory in the social sciences hypothesizes that as countries advance economically, their populations tend to become less religious, often leading to wider social change. Known as “secularization theory,” it particularly reflects the experience of Western European countries from the end of World War II to the present.

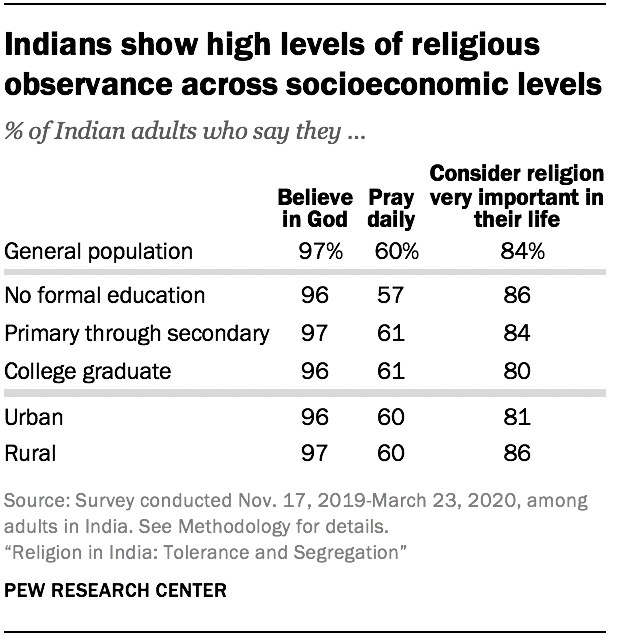

Despite rapid economic growth, India’s population so far shows few, if any, signs of losing its religion. For instance, both the Indian census and the new survey find virtually no growth in the minuscule share of people who claim no religious identity. And religion is prominent in the lives of Indians regardless of their socioeconomic status. Generally, across the country, there is little difference in personal religious observance between urban and rural residents or between those who are college educated versus those who are not. Overwhelming shares among all these groups say that religion is very important in their lives, that they pray regularly and that they believe in God.

Nearly all religious groups show the same patterns. The biggest exception is Christians, among whom those with higher education and those who reside in urban areas show somewhat lower levels of observance. For example, among Christians who have a college degree, 59% say religion is very important in their life, compared with 78% among those who have less education.

The survey does show a slight decline in the perceived importance of religion during the lifetime of respondents, though the vast majority of Indians indicate that religion remains central to their lives, and this is true among both younger and older adults.

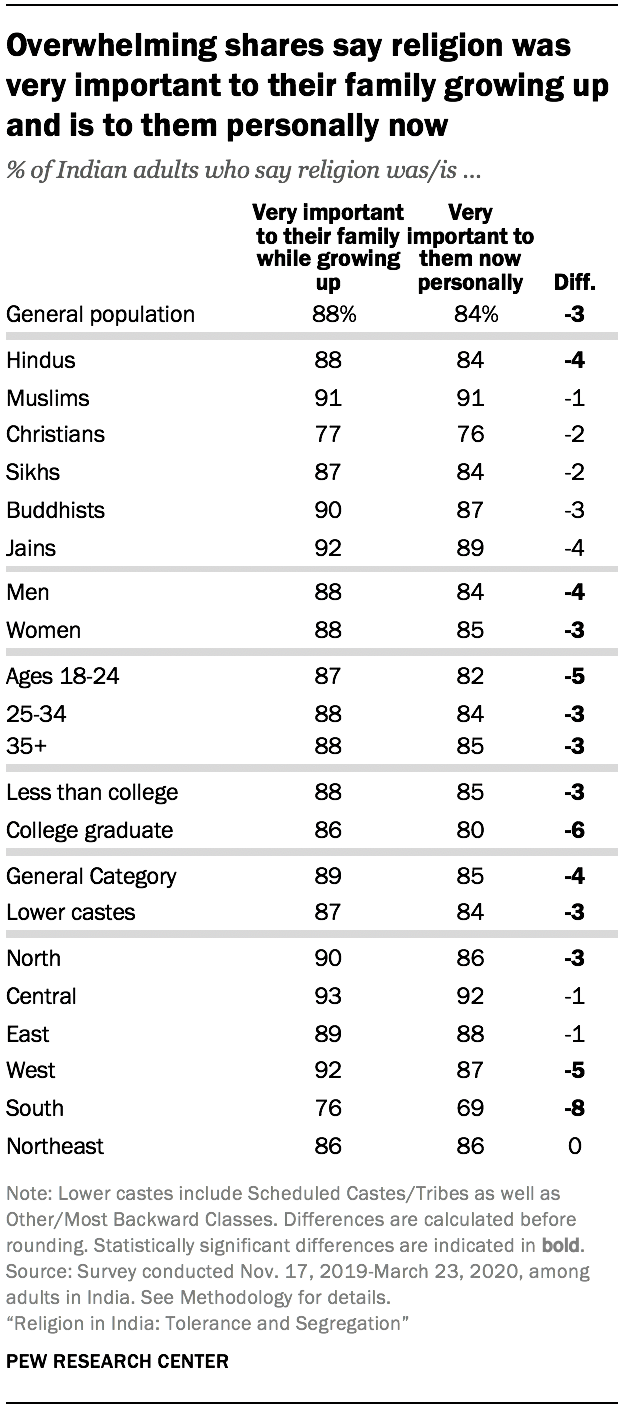

Nearly nine-in-ten Indian adults say religion was very important to their family when they were growing up (88%), while a slightly lower share say religion is very important to them now (84%). The pattern is identical when looking only at India’s majority Hindu population. Among Muslims in India, the same shares say religion was very important to their family growing up and is very important to them now (91% each).

The states of Southern India (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Puducherry, Tamil Nadu and Telangana) show the biggest downward trend in the perceived importance of religion over respondents’ lifetimes: 76% of Indians who live in the South say religion was very important to their family growing up, compared with 69% who say religion is personally very important to them now. Slight declines in the importance of religion, by this measure, also are seen in the Western part of the country (Goa, Gujarat and Maharashtra) and in the North, although large majorities in all regions of the country say religion is very important in their lives today.

Across India’s religious groups, widespread sharing of beliefs, practices, values

Despite a strong desire for religious segregation, India’s religious groups share patriotic feelings, cultural values and some religious beliefs. For instance, overwhelming shares across India’s religious communities say they are very proud to be Indian, and most agree that Indian culture is superior to others.

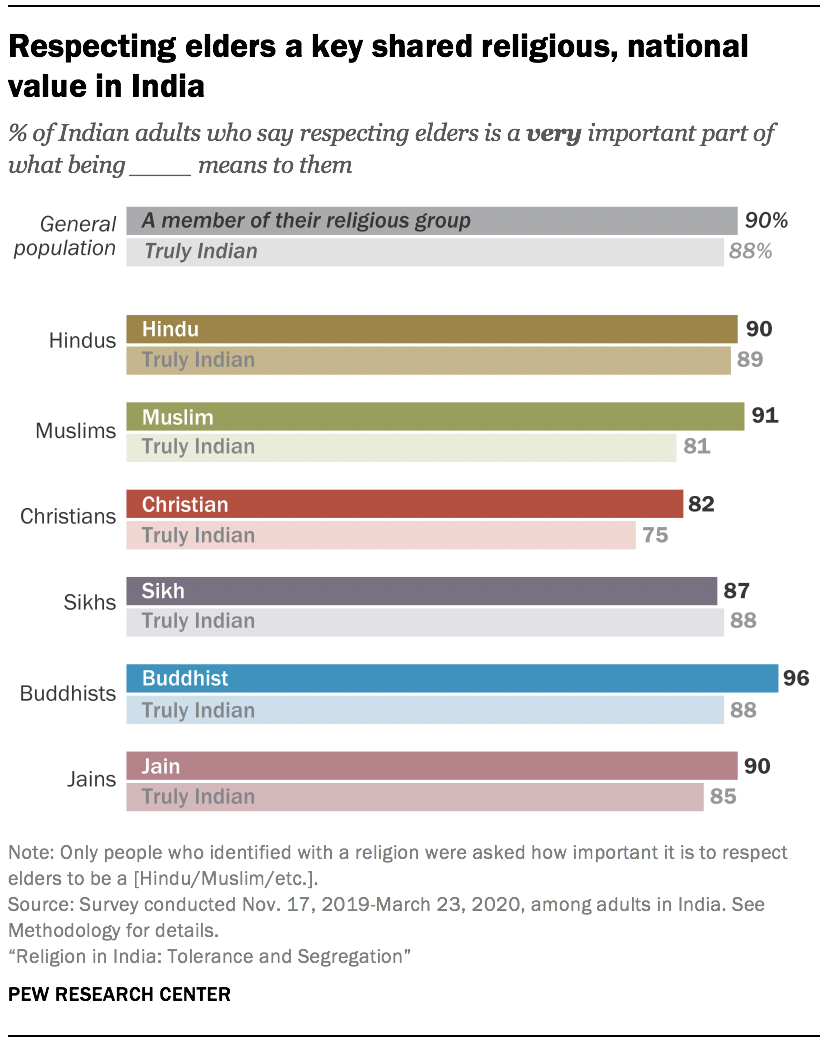

Similarly, Indians of different religious backgrounds hold elders in high respect. For instance, nine-in-ten or more Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and Jains say that respecting elders is very important to what being a member of their religious group means to them (e.g., for Hindus, it’s a very important part of their Hindu identity). Christians and Sikhs also overwhelmingly share this sentiment. And among all people surveyed in all six groups, three-quarters or more say that respecting elders is very important to being truly Indian.

Within all six religious groups, eight-in-ten or more also say that helping the poor and needy is a crucial part of their religious identity.

Beyond cultural parallels, many people mix traditions from multiple religions into their practices: As a result of living side by side for generations, India’s minority groups often engage in practices that are more closely associated with Hindu traditions than their own. For instance, many Muslim, Sikh and Christian women in India say they wear a bindi (a forehead marking, often worn by married women), even though putting on a bindi has Hindu origins.

Similarly, many people embrace beliefs not traditionally associated with their faith: Muslims in India are just as likely as Hindus to say they believe in karma (77% each), and 54% of Indian Christians share this view. 8 Nearly three-in-ten Muslims and Christians say they believe in reincarnation (27% and 29%, respectively). While these may seem like theological contradictions, for many Indians, calling oneself a Muslim or a Christian does not preclude believing in karma or reincarnation – beliefs that do not have a traditional, doctrinal basis in Islam or Christianity.

Most Muslims and Christians say they don’t participate in celebrations of Diwali, the Indian festival of lights that is traditionally celebrated by Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists. But substantial minorities of Christians (31%) and Muslims (20%) report that they do celebrate Diwali. Celebrating Diwali is especially common among Muslims in the West, where 39% say they participate in the festival, and in the South (33%).

Not only do some followers of all these religions participate in a celebration (Diwali) that consumes most of the country once a year, but some members of the majority Hindu community celebrate Muslim and Christian festivals, too: 7% of Indian Hindus say they celebrate the Muslim festival of Eid, and 17% celebrate Christmas.

Religious identity in India: Hindus divided on whether belief in God is required to be a Hindu, but most say eating beef is disqualifying

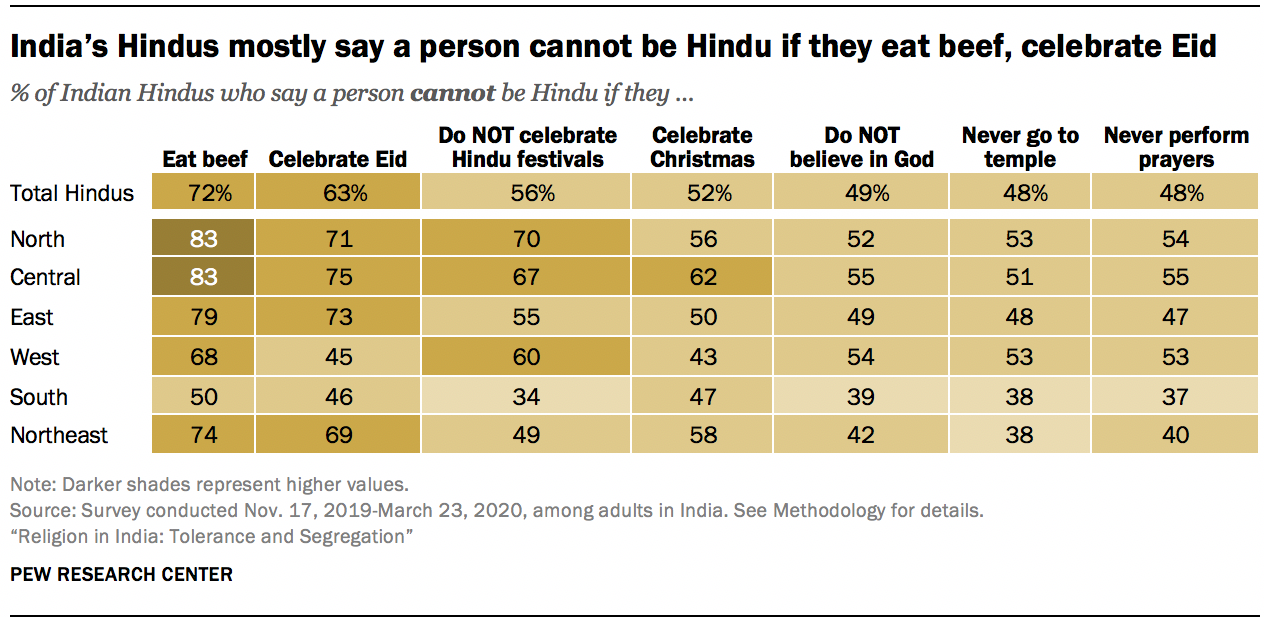

While there is some mixing of religious celebrations and traditions within India’s diverse population, many Hindus do not approve of this. In fact, while 17% of the nation’s Hindus say they participate in Christmas celebrations, about half of Hindus (52%) say that doing so disqualifies a person from being Hindu (compared with 35% who say a person canbe Hindu if they celebrate Christmas). An even greater share of Hindus (63%) say a person cannot be Hindu if they celebrate the Islamic festival of Eid – a view that is more widely held in Northern, Central, Eastern and Northeastern India than the South or West.

Hindus are divided on whether beliefs and practices such as believing in God, praying and going to the temple are necessary to be a Hindu. But one behavior that a clear majority of Indian Hindus feel is incompatible with Hinduism is eating beef: 72% of Hindus in India say a person who eats beef cannot be a Hindu. That is even higher than the percentages of Hindus who say a person cannot be Hindu if they reject belief in God (49%), never go to a temple (48%) or never perform prayers (48%).

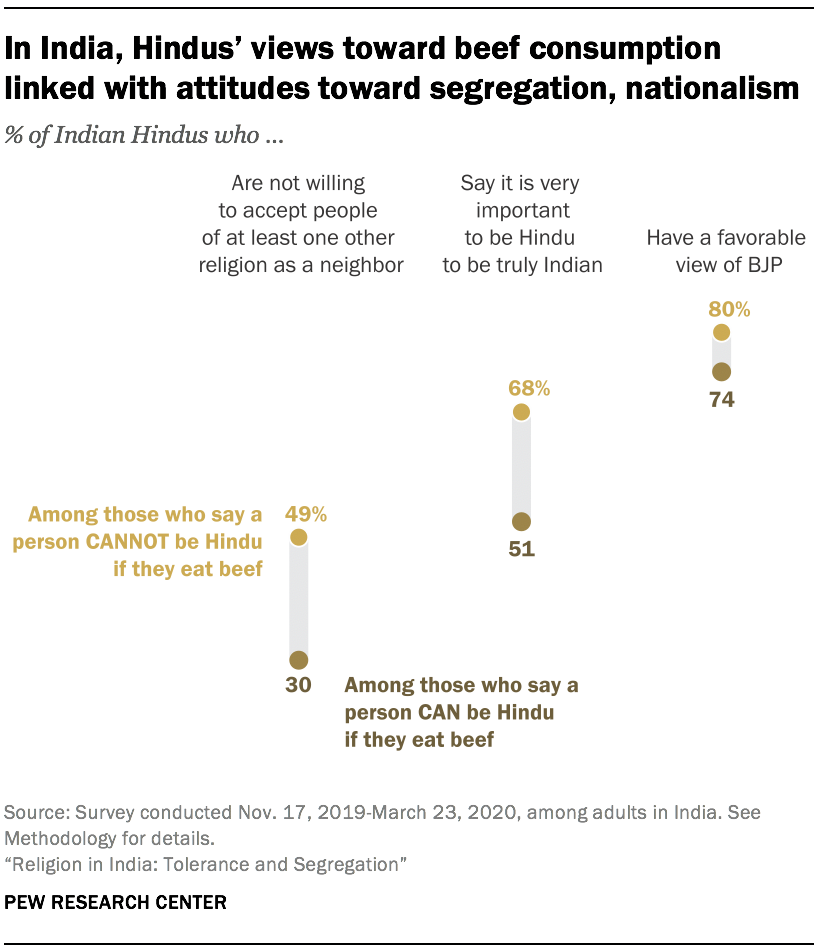

Attitudes toward beef appear to be part of a regional and cultural divide among Hindus: Southern Indian Hindus are considerably less likely than others to disqualify beef eaters from being Hindu (50% vs. 83% in the Northern and Central parts of the country). And, at least in part, Hindus’ views on beef and Hindu identity are linked with a preference for religious segregation and elements of Hindu nationalism. For example, Hindus who take a strong position against eating beef are more likely than others to say they would not accept followers of other religions as their neighbors (49% vs. 30%) and to say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian (68% vs. 51%).

Relatedly, 44% of Hindus say they are vegetarians, and an additional 33% say they abstain from eating certain meats. Hindus traditionally view cows as sacred, and laws pertaining to cow slaughter have been a recent flashpoint in India. At the same time, Hindus are not alone in linking beef consumption with religious identity: 82% of Sikhs and 85% of Jains surveyed say that a person who eats beef cannot be a member of their religious groups, either. A majority of Sikhs (59%) and fully 92% of Jains say they are vegetarians, including 67% of Jains who do not eat root vegetables. 9 (For more data on religion and dietary habits, see Chapter 10.)

Sidebar: People in the South differ from rest of the country in their views of religion, national identity

The survey consistently finds that people in the South (the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana, and the union territory of Puducherry) differ from Indians elsewhere in the country in their views on religion, politics and identity.

For example, by a variety of measures, people in the South are somewhat less religious than those in other regions – 69% say religion is very important in their lives, versus 92% in the Central part of the country. And 37% say they pray every day, compared with more than half of Indians in other regions. People in the South also are less segregated by religion or caste – whether that involves their friendship circles, the kind of neighbors they prefer or how they feel about intermarriage. (See Chapter 3.)

Hindu nationalist sentiments also appear to have less of a foothold in the South. Among Hindus, those in the South (42%) are far less likely than those in Central states (83%) or the North (69%) to say being Hindu is very important to be truly Indian. And in the 2019 parliamentary elections, the BJP’s lowest vote share came in the South. In the survey, just 19% of Hindus in the region say they voted for the BJP, compared with roughly two-thirds in the Northern (68%) and Central (65%) parts of the country who say they voted for the ruling party.

Culturally and politically, people in the South have pushed back against the BJP’s restrictions on cow slaughter and efforts to nationalize the Hindi language. These factors may contribute to the BJP’s lower popularity in the South, where more people prefer regional parties or the Indian National Congress party.

These differences in attitudes and practices exist in a wider context of economic disparities between the South and other regions of the country. Over time, Southern states have seen stronger economic growth than the Northern and Central parts of the country. And women and people belonging to lower castes in the South have fared better economically than their counterparts elsewhere in the country. Even though three-in-ten people in the South say there is widespread caste discrimination in India, the region also has a history of anti-caste movements. Indeed, one author has attributed the economic growth of the South largely to the flattening of caste hierarchies.

Muslim identity in India

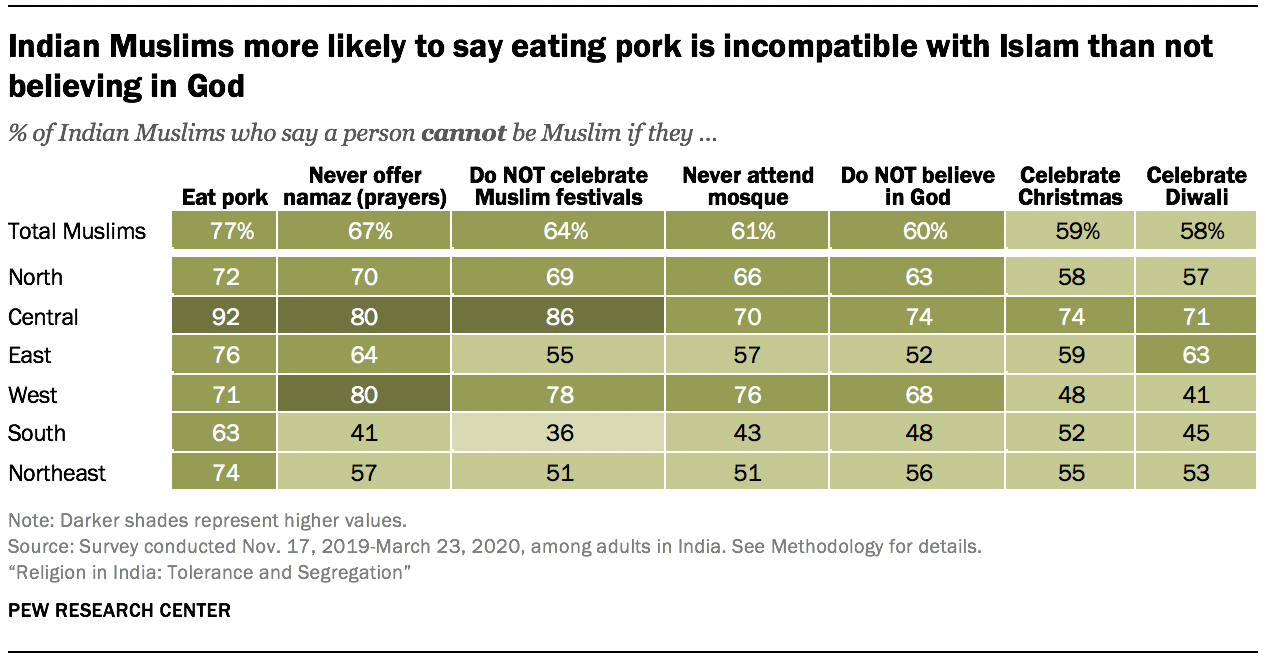

Most Muslims in India say a person cannot be Muslim if they never pray or attend a mosque. Similarly, about six-in-ten say that celebrating Diwali or Christmas is incompatible with being a member of the Muslim community. At the same time, a substantial minority express a degree of open-mindedness on who can be a Muslim, with fully one-third (34%) saying a person can be Muslim even if they don’t believe in God. (The survey finds that 6% of self-described Muslims in India say they do not believe in God; see “Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived” above.)

Like Hindus, Muslims have dietary restrictions that resonate as powerful markers of identity. Three-quarters of Indian Muslims (77%) say that a person cannot be Muslim if they eat pork, which is even higher than the share who say a person cannot be Muslim if they do not believe in God (60%) or never attend mosque (61%).

Indian Muslims also report high levels of religious commitment by a host of conventional measures: 91% say religion is very important in their lives, two-thirds (66%) say they pray at least once a day, and seven-in-ten say they attend mosque at least once a week – with even higher attendance among Muslim men (93%).

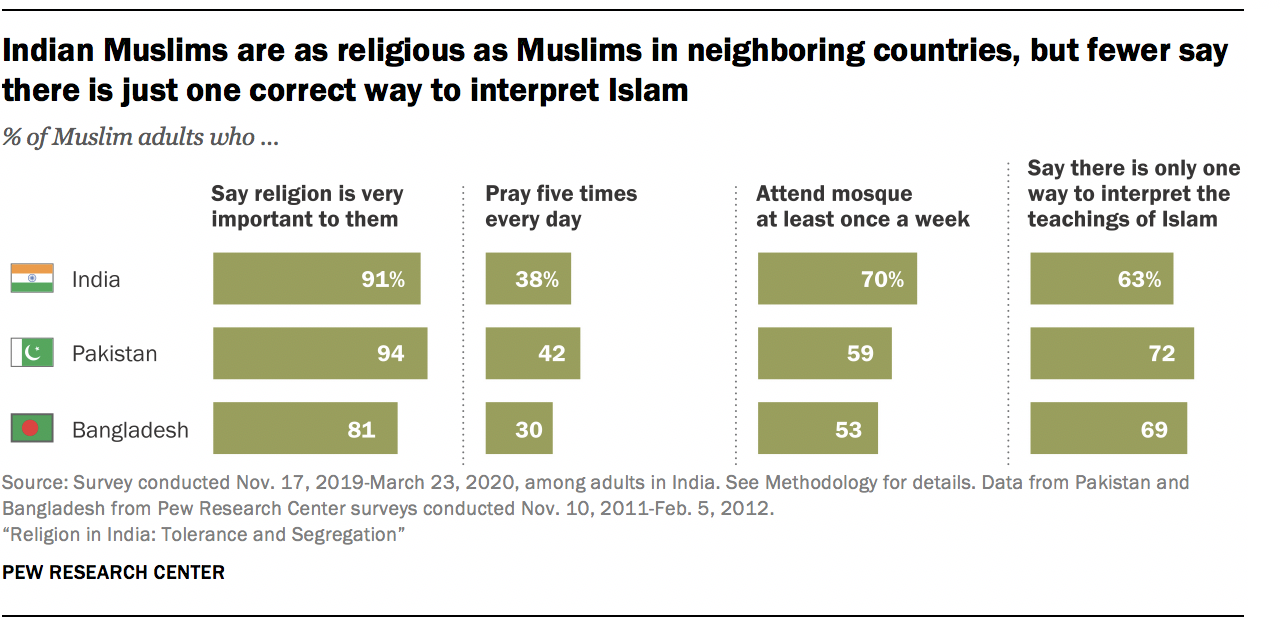

By all these measures, Indian Muslims are broadly comparable to Muslims in the neighboring Muslim-majority countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in those countries in late 2011 and early 2012. In Pakistan, for example, 94% of Muslims said religion is very important in their lives, while 81% of Bangladeshi Muslims said the same. Muslims in India are somewhat more likely than those elsewhere in South Asia to say they regularly worship at a mosque (70% in India vs. 59% in Pakistan and 53% in Bangladesh), with the difference mainly driven by the share of women who attend.

At the same time, Muslims in India are slightly less likely to say there is “only one true” interpretation of Islam (72% in Pakistan, 69% in Bangladesh, 63% in India), as opposed to multiple interpretations.

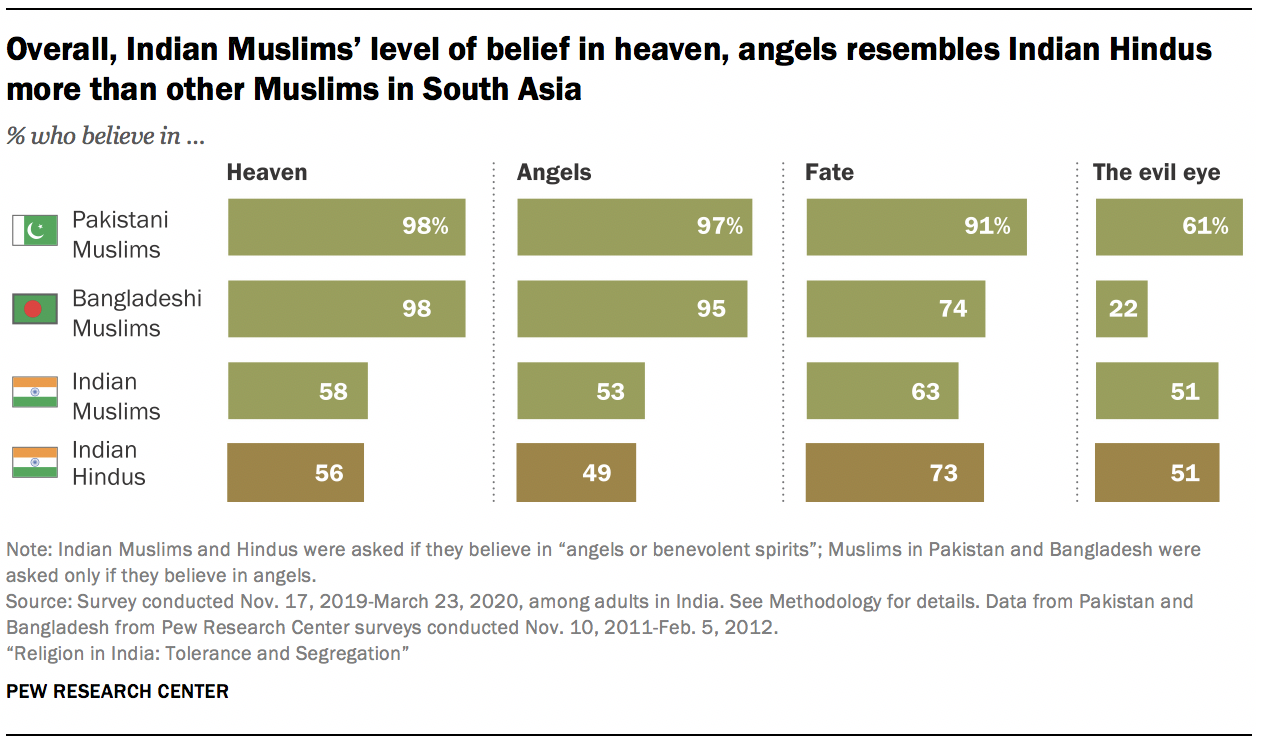

When it comes to their religious beliefs, Indian Muslims in some ways resemble Indian Hindus more than they resemble Muslims in neighboring countries. For example, Muslims in Pakistan and Bangladesh almost universally say they believe in heaven and angels, but Indian Muslims seem more skeptical: 58% say they believe in heaven and 53% express belief in angels. Among Indian Hindus, similarly, 56% believe in heaven and 49% believe in angels.

Majority of Muslim women in India oppose ‘triple talaq’ (Islamic divorce)

Many Indian Muslims historically have followed the Hanafi school of thought, which for centuries allowed men to divorce their wives by saying “talaq” (which translates as “divorce” in Arabic and Urdu) three times. Traditionally, there was supposed to be a waiting period and attempts at reconciliation in between each use of the word, and it was deeply frowned upon (though technically permissible) for a man to pronounce “talaq” three times quickly in a row. India’s Supreme Court ruled triple talaq unconstitutional in 2017, and it was banned by legislation in 2019.

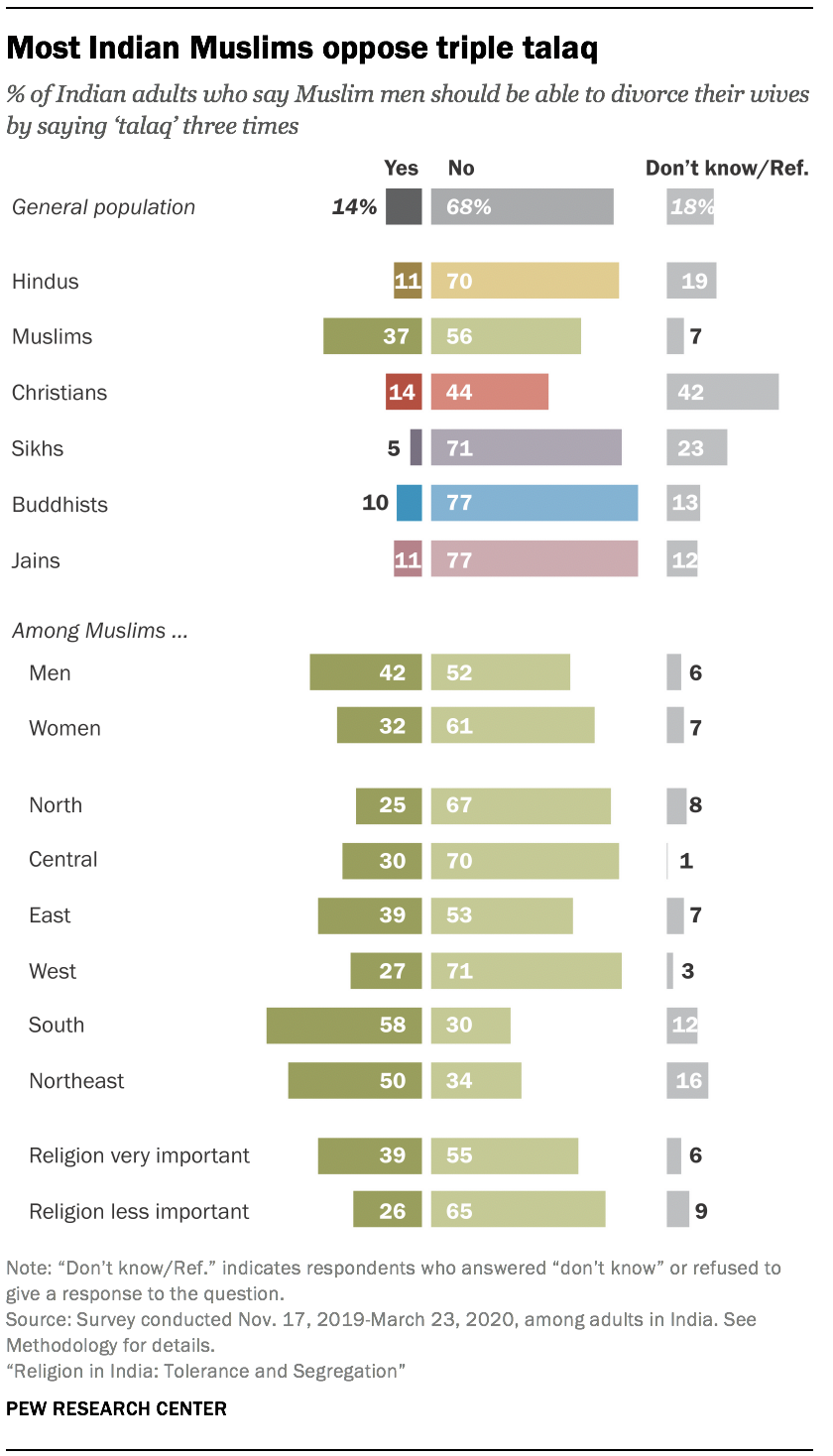

Most Indian Muslims (56%) say Muslim men should not be allowed to divorce this way. Still, 37% of Indian Muslims say they support triple talaq, with Muslim men (42%) more likely than Muslim women (32%) to take this position. A majority of Muslim women (61%) oppose triple talaq.

Highly religious Muslims – i.e., those who say religion is very important in their lives – also are more likely than other Muslims to say Muslim men should be able to divorce their wives simply by saying “talaq” three times (39% vs. 26%).

Triple talaq seems to have the most support among Muslims in the Southern and Northeastern regions of India, where half or more of Muslims say it should be legal (58% and 50%, respectively), although 12% of Muslims in the South and 16% in the Northeast do not take a position on the issue either way.

Sikhs are proud to be Punjabi and Indian

Sikhism is one of four major religions – along with Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism – that originated on the Indian subcontinent. The Sikh religion emerged in Punjab in the 15th century, when Guru Nanak, who is revered as the founder of Sikhism, became the first in a succession of 10 gurus (teachers) in the religion.

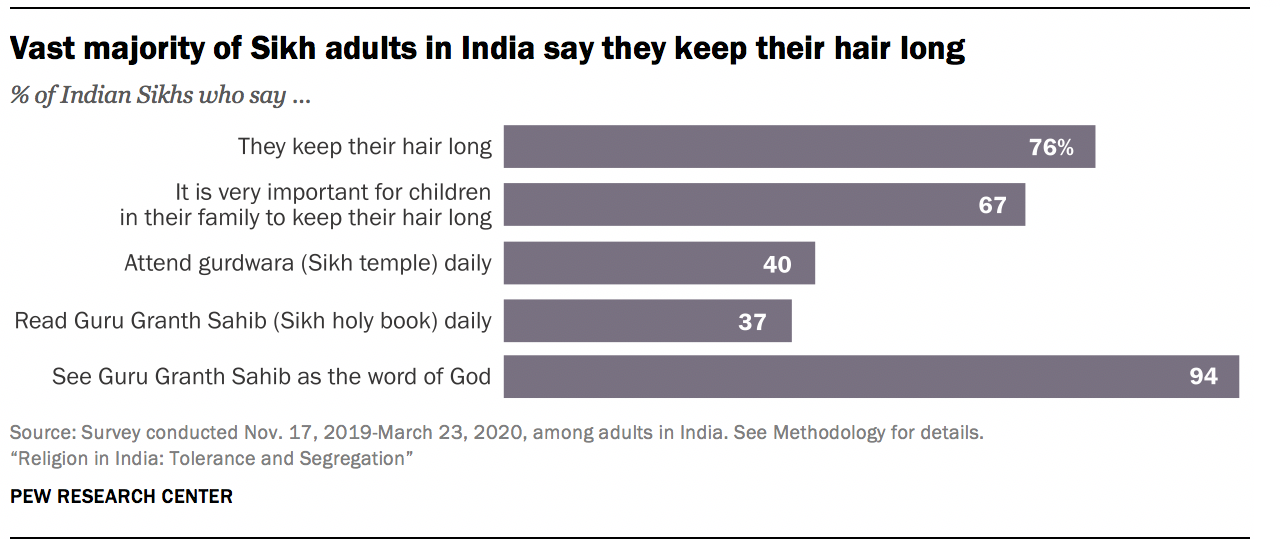

Today, India’s Sikhs remain concentrated in the state of Punjab. One feature of the Sikh religion is a distinctive sense of community, also known as “Khalsa” (which translates as “ones who are pure”). Observant Sikhs differentiate themselves from others in several ways, including keeping their hair uncut. Today, about three-quarters of Sikh men and women in India say they keep their hair long (76%), and two-thirds say it is very important to them that children in their families also keep their hair long (67%). (For more analysis of Sikhs’ views on passing religious traditions on to their children, see Chapter 8.)

Sikhs are more likely than Indian adults overall to say they attend religious services every day – 40% of Sikhs say they go to the gurdwara (Sikh house of worship) daily. By comparison, 14% of Hindus say they go to a Hindu temple every day. Moreover, the vast majority of Sikhs (94%) regard their holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, as the word of God, and many (37%) say they read it, or listen to recitations of it, every day.

Sikhs in India also incorporate other religious traditions into their practice. Some Sikhs (9%) say they follow Sufi orders, which are linked with Islam, and about half (52%) say they have a lot in common with Hindus. Roughly one-in-five Indian Sikhs say they have prayed, meditated or performed a ritual at a Hindu temple.

Sikh-Hindu relations were marked by violence in the 1970s and 1980s, when demands for a separate Sikh state covering the Punjab regions in both India and Pakistan (also known as the Khalistan movement) reached their apex. In 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards as revenge for Indian paramilitary forces storming the Sikh Golden Temple in pursuit of Sikh militants. Anti-Sikh riots ensued in Northern India, especially in the state of Punjab.

According to the Indian census, the vast majority of Sikhs in India (77%) still live in Punjab, where Sikhs make up 58% of the adult population. And 93% of Punjabi Sikhs say they are very proud to live in the state.

Sikhs also are overwhelmingly proud of their Indian identity. A near-universal share of Sikhs say they are very proud to be Indian (95%), and the vast majority (70%) say a person who disrespects India cannot be a Sikh. And like India’s other religious groups, most Sikhs do not see evidence of widespread discrimination against their community – just 14% say Sikhs face a lot of discrimination in India, and 18% say they personally have faced religious discrimination in the last year.

At the same time, Sikhs are more likely than other religious communities to see communal violence as a very big problem in the country. Nearly eight-in-ten Sikhs (78%) rate communal violence as a major issue, compared with 65% of Hindus and Muslims.

The BJP has attempted to financially compensate Sikhs for some of the violence that occurred in 1984 after Indira Gandhi’s assassination, but relatively few Sikh voters (19%) report having voted for the BJP in the 2019 parliamentary elections. The survey finds that 33% of Sikhs preferred the Indian National Congress Party – Gandhi’s party.

- Ahmed, Hilal. 2019. “Siyasi Muslims: A story of political Islams in India.” ↩

- All survey respondents, regardless of religion, were asked, “Are you from a General Category, Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Class?” By contrast, in the 2011 census of India, only Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists could be enumerated as members of Scheduled Castes, while Scheduled Tribes could include followers of all religions. General Category and Other Backward Classes were not measured in the census. A detailed analysis of differences between 2011 census data on caste and survey data can be found here. ↩

- According to the 2004 and 2009 National Election Studies by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), roughly half of Indians or more said that marriages of boys and girls from different castes should be banned. In 2004, a majority also said this about people from different religions. ↩

- In both the 2004 and 2009 National Election Studies (organized by CSDS), roughly half of Indians said that “There should be a legal ban on religious conversions.” ↩

- This includes 0.2% of all Indian adults who now identify as Hindu but give an ambiguous response on how they were raised – either saying “some other religion” or saying they don’t know their childhood religion. ↩

- Puja is a specific worship ritual that involves prayer along with rites like offering flowers and food, using vermillion, singing and chanting. ↩

- Fifteen named deities were available for selection, though no answer options were read aloud. Respondents could select up to three of those 15 deities by naming them or selecting the corresponding image shown on a card. The answer option “another god” was available on the card or if any other deity name was volunteered by the respondent. Other possible answer options included “I do not have a god I feel closest to” and “I have many personal gods,” though neither was on the card. See the questionnaire or topline for the full list of gods offered. ↩

- The religious origins of karma are debated by scholars, but the concept has deep roots in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism. ↩

- For an analysis of Jain theology on the concept of jiva (soul) see Chapple, Christopher K. 2014. “Life All Around: Soul in Jainism.” In Biernacki, Loriliai and Philip Clayton, eds. “Panentheism Across the World’s Traditions.” ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings